As I have learnt over and over again, the direct involvement of local communities is a vital facet of affecting change and conservation. Nowhere I have been reflects this more than here in Baja California (BCS). Before the 1920s, Mexico’s waters were filled with fishing vessels from more powerful countries fishing with no regulations. So in 1948 the government of Mexico started to create a structure to manage their fisheries through the empowerment of their fishing communities to create a group of cooperatives that would work together. In theory these cooperatives would ensure that good fishing practices were used, and decide prices on their products so that no buyer could undercut and thereby weaken their structure. Here in BCS this has led to an exemplary system where solidarity leads to long term benefits! And even though my visit here was only two weeks I could see why.

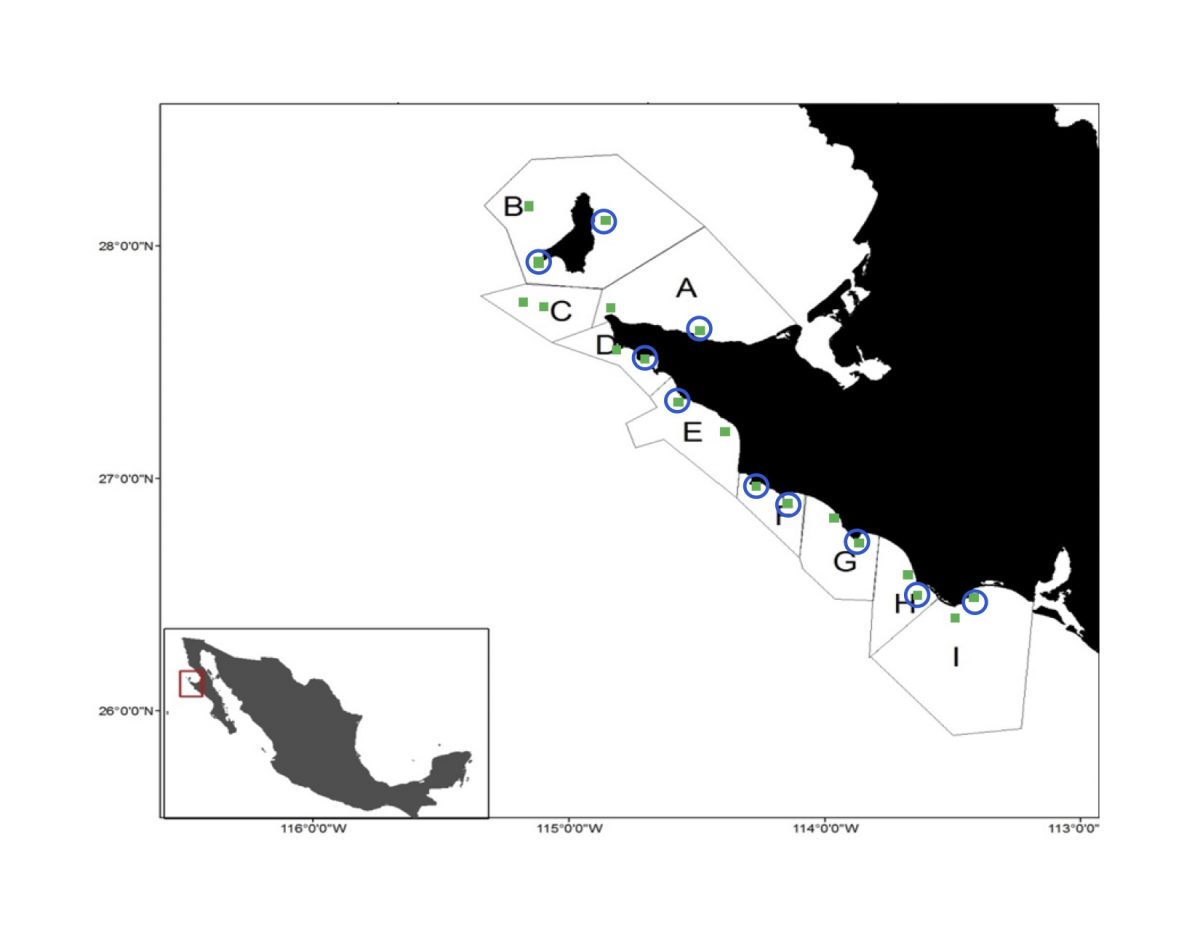

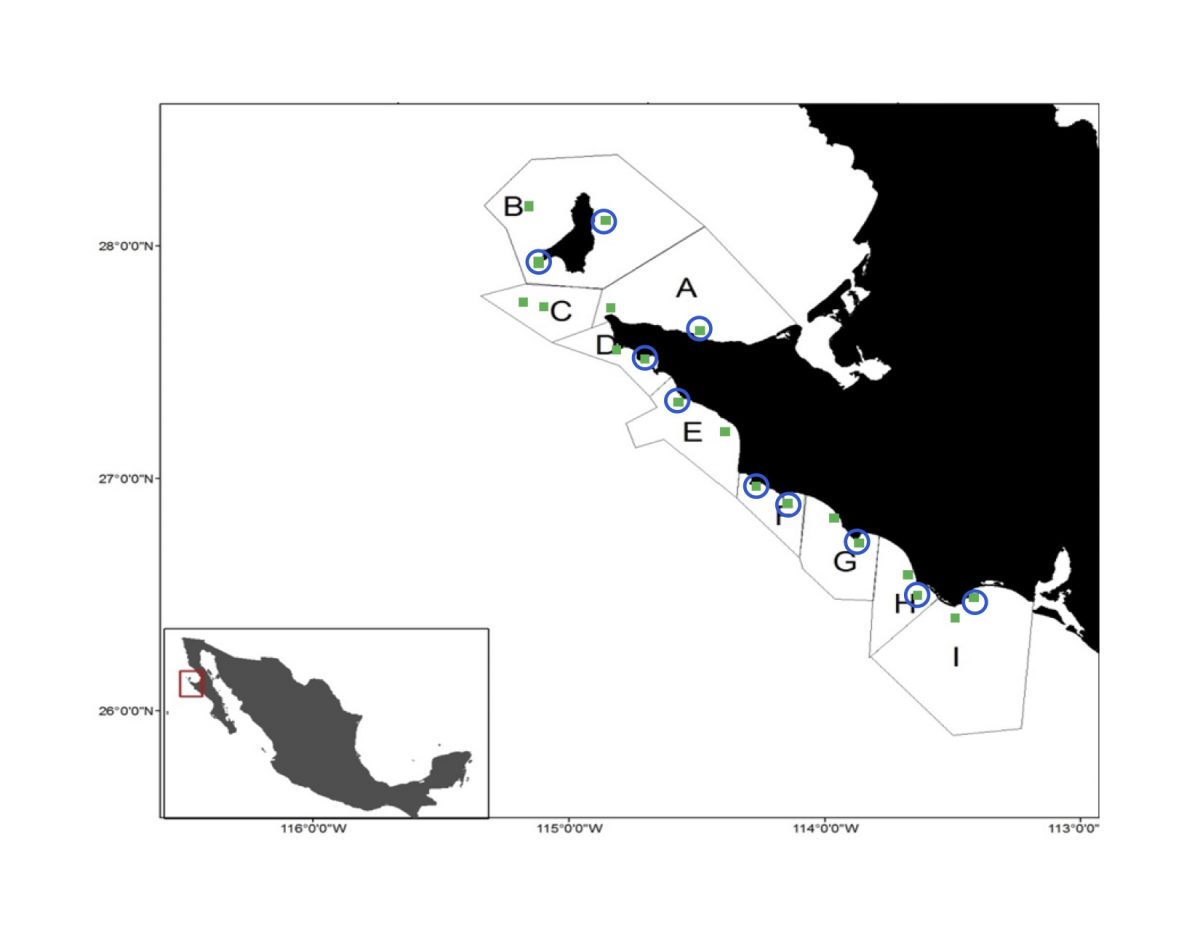

I am here visiting Communidad y Biodiversidad (COBI) a Mexico based NGO that has been active in marine conservation with participation of Mexican fisheries for 20 years. I joined them on one of their bi-annual sensor maintenance trips where over 8 days we switched out 8 sensors in 8 different communities.

I flew into La Paz, where they have their BCS office and spent a day meeting with their staff to go over their main goals and mandates for their work. They are:

1) To establish community committees with local leaders

2) To work with communities to establish sustainable fishery practices

3) To establish Marine Reserves

4) To work with policy makers to incorporate local issues of fishing and conservation

COBI works all over Mexico with offices in La Paz, Guaymas, Sonora, Cancun, Quintana Roo and in the Yucatan Peninsula. Through many different area-specific and centralized projects they are working hard to achieve these goals. Specifically, on the Baja Peninsula they work with 12 cooperatives and over 1000 individuals. They also have 13 different fishery improvement projects (FIP) running right now throughout Mexico. Working together with the fishers of each community, these projects include creation of marine reserves, artificial reefs, lab-rearing abalone and other shellfish like clams and oysters. The animals are subsequently returned to their environment where based on communal decisions they remain untouched or are harvested once they reach proper size.

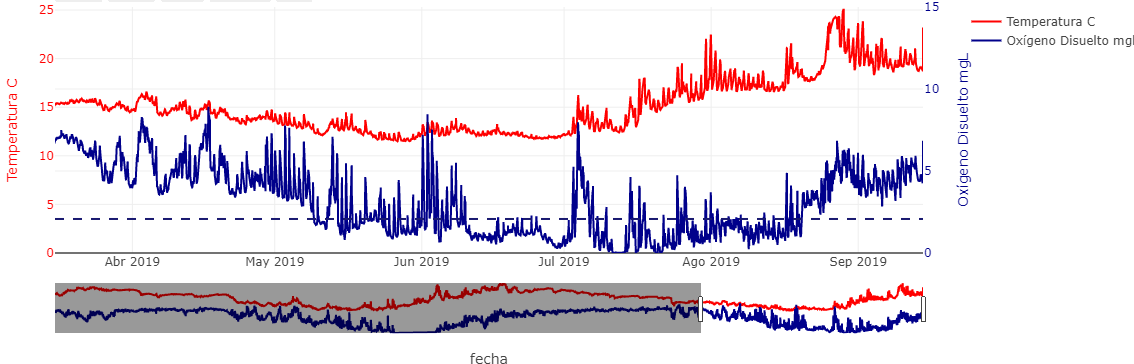

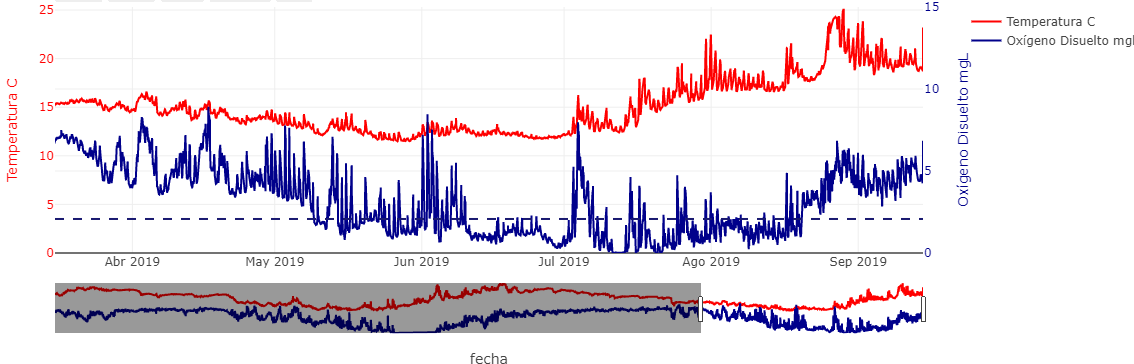

Arturo Hernandez Velasco Jefe de Reservas Marinas (Chief of the Marine Reserve Program), Eduardo Diaz Mora; assistente de reservas marinas (Research assistant for Marine Reserves), and I left la Paz and drove about 10 hours Northwest to the small community of Bahia Tortugas. This was hands down one of the most beautiful drives of my life!! In conjunction with researchers from Stanford University, COBI has installed 2 sensors per fishing cooperative in this region and the aim of the trip was to upload the data from each sensor and redeploy it for another season. These sensors sample temperature and dissolved oxygen in the water every ten minutes. This data is shared with the local cooperatives and through this they themselves can make decisions on how their fisheries will be managed throughout the year.

Based on historical data and knowledge, the ability of the fishers to understand what might happen based on this abiotic data is brilliant. For example, one day on Cedros Island one of the sensors showed that the previous six months had a relatively high average temperature. When we mentioned that to one of the fisherman he immediately responded with “oh ok so this will be a good year for lobster, but not so good for the abalone…” I was so impressed. Interactions like this and conversations with fishers in different communities have demonstrated that here they understand the importance of a functioning ecosystem and what some of the indicators of this are.

Talking to Ramon about fishery challenges

Edu and Ramon talk about the new dataset from the sensors on Natividad

COBI has created a system where members of each cooperative are trained to carry out ecological surveys. They look at algae, invertebrates, fish and habitat structure within their fishing areas and if the cooperative has a marine reserve they do the same survey there as well. This allows the fishers themselves to see differences between these areas and the effects of protection, and also to be able to tease out what issues in the ecosystem fishing causes and what could be caused by other stressors such as changes in climate or periods of anoxia. These hypotheses are then also corroborated by abiotic data that these sensors provide.

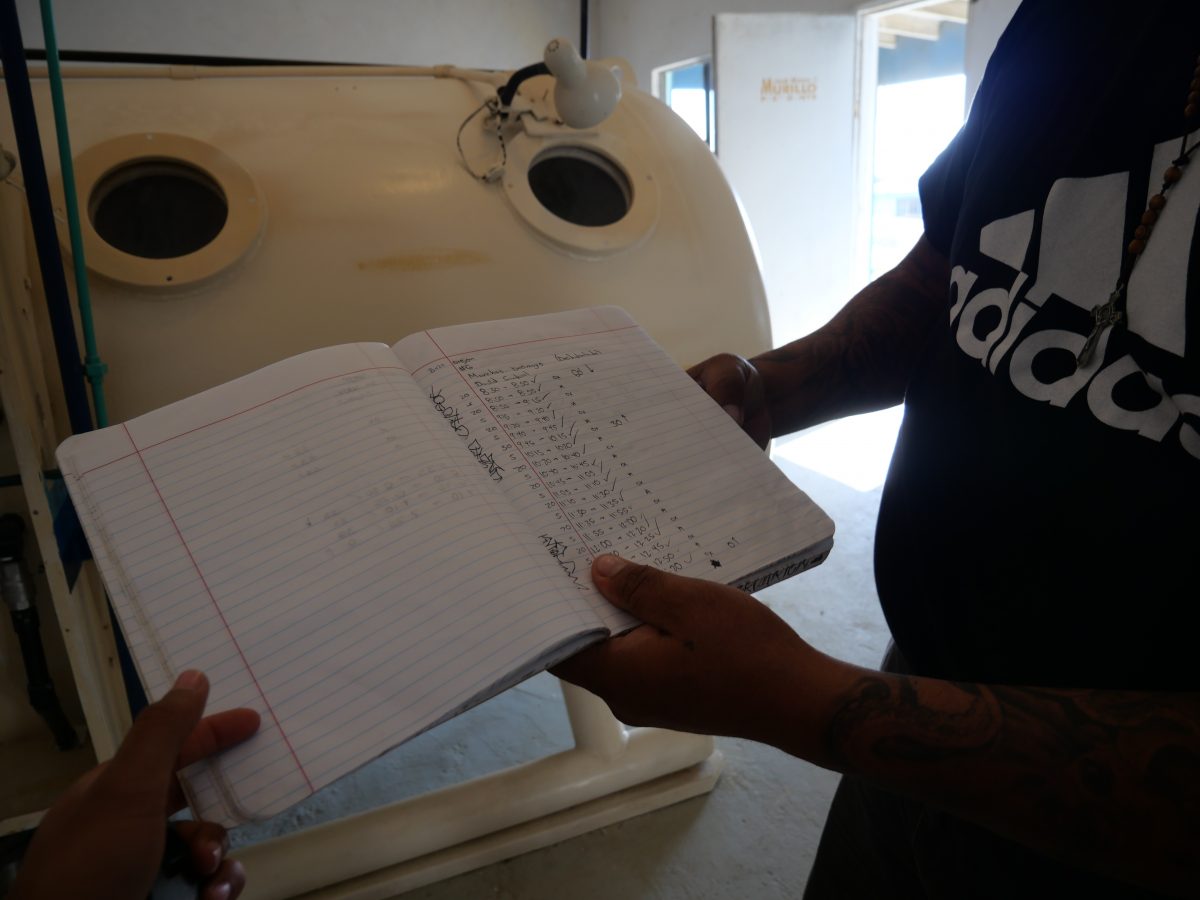

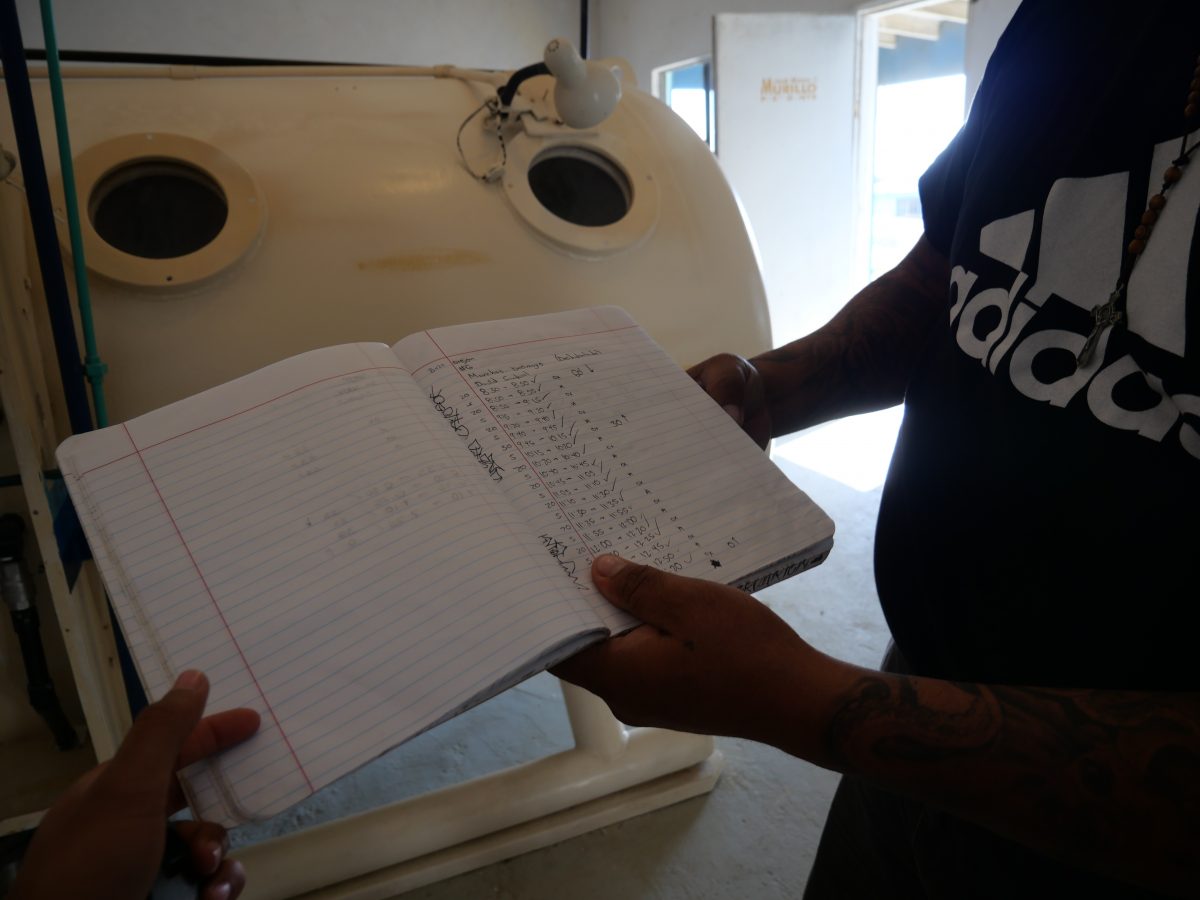

One of the communities we visited was a small island called Isla Natividad. They are a small and obviously tight –knit community (less than 500). Since the 1940s they have had their own fishing cooperative called SCPP Divers and fishers of Baja California through which they have their own company called “Island Pacific”. This cooperative has been incredibly successful and together they have built their own abalone and shellfish cannery, as well as a laboratory to cultivate abalone larvae for transplant on reefs. They also have their own hyperbaric chamber with trained tenders, so they can provide their divers with adequate first aid when the need arises. This place is AMAZING! COBI has had a presence here for the last 13 years and they are one of the first communities where they trained fisherman to do ecological monitoring on the Baja Peninsula. They now have two marine reserves in ecologically important locations that were chosen based on oceanographic and biological information that was collected and presented by COBI.

One of the Dive tenders of Isla Natividads Hyperbaric Chamber

The Chamber can hold up to 6 people

Log book – this chamber is used regularly!

They are also one of the pilot sites for a COBI initiative called “Igualdad de Genero en el Mar” or “Gender Equality in the sea.” As in most places in the world, fishing is a generally male occupation. Here, however, through this program COBI aims to engage and empower women within the community as well as shifting the male perspective that the work can or should only be done by them! Seven years ago COBI trained 6 women on the island to conduct ecological surveys and they love it! They have formed a group called Sirenas de Natividad and love to share their knowledge. One of them; Esmeralda Alvañes has gotten her rescue diver ticket and is aiming to lead training dives throughout the year in preparation for surveys. She also is starting a Hand Crafting company to make jewelry and other things out of the abalone shells from their abalone farm.

The community heavily relies on the Abalone fishery, and huge el Nino, or “The Blob” of 2013-15 had a devastating impact on their populations. For those of you that don’t know, the el Nino is a climate cycle that happens every 2-5 years with a global impact on weather patterns. Five years ago, the el Nino was one of the largest ever recorded and the mass of warm water that came with it up the pacific coast destroyed many things in its path. The snail and abalone fishery in Natividad totally collapsed with this event due to the compounding of three factors:

Arturo so Happy

Learning about the two local Abalone species

This lab is where abalone are brought to reach maturity

- Warm water leading to less kelp being able to survive and thus a decrease food and mechanical shelter

- The warm water and loss of shelter from kelps leading to less success for planktonic larvae to become settled juveniles

- The warm water increasing areas and time periods of anoxia leading to less survival

Filmmaker Gustavo M. Ballesté made a documentary on this phenomenon that beautifully illustrates the nuances and many consequences of our changing climate in Mexico. Since this event, the community has adapted, and through strategy and strict self-governance of fishing practices, they are seeing recovery in a mere 3 years. However, the community is very aware that historical levels will never again be seen, and that practices need to change permanently in order for this resource to continue to provide for their communities. A paper by COBI’s affiliates at Stanford found that when faced with increasing uncertainty, resource users choose to reduce harvest to compensate for future declines.

This is a hopeful conclusion for me! In this time of crisis, I am often depressed by those who choose to pull the wool over their eyes. The Baja Peninsula is a crazy, beautiful place where the desert meets the sea. When the terrestrial environment is so harsh, people must rely on the sea. Fishing is a vital aspect of the economy here, and the communities are clearly working together to adapt and to mitigate the effects of climate change as it affects their lives, and livelihoods. What I think makes this system so unique is that these fisheries are largely self governed, and the fishermen are divers themselves, and thus can see and understand the changes happening around them. For this reason organisations like COBI are vital to provide knowledge of new techniques, and data in order to help the cooperatives adopt new practices. And luckily the fishing cooperatives here are willing to learn and change in order to preserve the resources so important to their survival.

Thank you to COBI, and all of my sponsors for allowing me to visit these incredible communities!

Check out this National Geo Article About the unique fisheries of Baja

Ciencia por la Gente

Como he aprendido una tras otra vez, la participación directa de las comunidades locales es una faceta fundamental a favor del cambio y la conservación. No hay otro lugar en donde he estado que lo reflejea tanto como aquí en Baja California Sur. Antes de la década de 1920, las aguas de México se llenaban de barcos pesqueros de países con más poder y pescaban sin regulaciones. Así que en la década de 1930, el gobierno de México comenzó a crear una estructura para gestionar sus pesquerías a través del empoderamiento de sus comunidades pesqueras con el fin de crear un grupo de cooperativas que pudieran trabajar juntas. En teoría, tales cooperativas garantizarían que se utilicen buenas prácticas de pesca y docidan los precios de sus productos para que ningún comprador pudiera venderlos a precios más bajos y así debilitar su estructura. En BCS esto ha llevado a un sistema ejemplar donde la solidaridad resulta en beneficios a largo plazo. Con apenas dos semanas aquí, ahora entiendo por qué es así.

Estoy aquí visitando a Comunidad y Biodiversidad (COBI), que es una ONG con sede en México que ha participado activamente en la conservación marina con la participación de pescadores mexicanos durante 20 años. Me junté con ellos durante uno de sus viajes bianuales de mantenimiento de sensores oceanográficos MiniDOT. Durante 8 días cambiamos 8 sensores en 8 comunidades diferentes.

Llegué en avión a La Paz, donde está la oficina de COBI en BCS, y pasé el día conociendo al equipo y revisando sus objetivos y mandatos principales.Estos son:

1) Establecer comités comunitarios con líderes locales

2) Trabajar con las comunidades para favorecer prácticas pesqueras sostenibles

3) Establecer y monitorear reservas marinas

4) Trabajar junto con los formuladores de políticas para incorporar los problemas locales de pesca y de conservación.

COBI trabaja en todo México y tiene oficinas en La Paz, Baja California Sur; Guaymas, Sonora; Cancún, Quintana Roo y en Mérida, Yucatán. Están trabajando duro para lograr sus objetivos por medio de varios proyectos en áreas específicas y centralizadas. En la península de Baja California, por ejemplo, trabajan con 12 cooperativas y más de 1,000 personas. Además, actualmente tienen 13 proyectos diferentes de mejora pesquera distintos (FIP en inglés) en todo del Mexico. Junto los pescadores de cada comunidad trabajan con proyectos de conservación marina los cuales incluyen reservas marinas, arrecifes artificiales, crías en laboratorio de abulón y otros mariscos como almejas y ostiones. De acuerdo con decisiones comunales, los pescadores diseñan, evalúan y vigilan sus reservas marinas, para el caso de algunas pesquerías siguen estándares del MSCC con la finalidad de conservar y preservar sus pesquerías, respetando tallas, vedas y reproducción de las especies.

Arturo Hernandez Velasco, Jefe de Reservas Marinas; Eduardo Diaz Mora, Asistente de Reservas Marinas, y yo conducimos diez horas desde La Paz hacia el noroeste a una pequeña comunidad llamada Bahía Tortugas. Esto fue sin duda uno de los recorridos más hermosos que he hecho en mi vida. En conjunto con investigadores de la Universidad de Stanford, COBI ha instalado 2 sensores por cada cooperativa pesquera en esta región y el objetivo del viaje era descargar los datos de cada sensor y volver a colocarlos para otra temporada. Estos sensores toman datos de temperatura y oxígeno disuelto en el agua cada diez minutos. Estos datos se comparten con las cooperativas locales, y, a través de esto ellos mismos pueden tomar decisiones sobre cómo gestionar sus pesquerías en el transcurso del año.

Gracias a los datos y el conocimiento histórico, la capacidad de los pescadores para entender lo que podría suceder según estos datos abióticos es increíble. Por ejemplo un día que estábamos en la Isla Cedros uno de los sensores mostró que en los últimos seis meses había una temperatura promedio relativamente alta. Cuando se lo mencionamos a uno de los pescadores, su respuesta inmediata fue “ah, OK, así que habrá buena temporada de pesca de langosta, pero no tan buena para pesca de abulón.” Me impresionó mucho. Interacciones como esta junto con conversaciones que he tenido con pescadores en diferentes comunidades me han confirmado que aquí en BCS entienden la importancia de un ecosistema funcional y cuáles son algunos de los indicadores de esto.

Hablando con Ramon acerca de los retos de las pesquerias

Edu y Ramon hablando sobre los nuevos datos de los sensores en Natividad

COBI ha creado un sistema en donde capacitan a los miembros de cada cooperativa para realizar evaluaciones ecológicas. Analizan algas, invertebrados, peces y la estructura del hábitat dentro de sus áreas de pesca y, si la cooperativa tiene una reserva marina, también realizan la misma evaluacion allí. Esto permite a los propios pescadores ver las diferencias entre estas áreas y los efectos de la protección, así como ser capaces de identificar cuáles problemas son causados por la pesca del ecosistema y cuáles problemas son causados por otros factores estresantes tales como cambios en el clima o periodos de anoxia. Estas hipótesis también se corroboran con datos abióticos proporcionados por estos sensores.

Una de las comunidades que visitamos era una pequeña isla llamada Isla Natividad. Es una comunidad obviamente pequeña y unida (no más de 500 habitantes). Desde la década de 1940 han manejado su propia cooperativa pesquera llamada SCPP Buzos y pescadores de la Baja California, llegando a tener su propia marca de mariscos “Island Pacific”. Esta cooperativa ha sido increíblemente exitosa y juntos han construido su propia conservera de abulón y mariscos, así como un laboratorio para cultivar larvas de abulón para trasplante en arrecifes. También tienen su propia cámara hiperbárica con licitaciones capacitadas, para que puedan proporcionar primeros auxilios a sus buceadores cuando sea necesario. ¡Este lugar es increíble! COBI ha estado presente aquí durante los últimos 13 años y son una de las primeras comunidades donde capacitaron a los pescadores para hacer un monitoreo ecológico en la Península de Baja California. Ahora tienen dos reservas marinas en lugares con importancia ecológica, que fueron elegidos con base en información oceanográfica y biológica registrada y presentada por COBI y por pescadores de la isla Natividad.

Uno de los operadores de la cámara hiperbarica

La cámara puede soportar 6 personas

Libro de registro- Esta cámara es usada regularmente!

También es uno de los sitios pilotos de una iniciativa suya llamada “Igualdad de Género en el Mar”. Como en la mayoría de los lugares del mundo, la pesca es un trabajo generalmente masculino. Sin embargo, este programa de COBI tiene como objetivo involucrar y empoderar a las mujeres dentro de la comunidad, así como cambiar la perspectiva masculina que el trabajo solo puede o debe ser realizado por los hombres. Hace siete años, COBI entrenó a 6 mujeres para que realicen evaluaciones ecológicas y les encanta. Han formado un grupo llamado Sirenas de Natividad y les encanta compartir sus conocimientos. Una de ellas, Esmeralda Albañes, obtuvo su certificación de Buzo de Rescate y tiene como objetivo guiar buceos de entrenamiento durante todo el año en preparación para las evaluaciones. Ella también está iniciando una empresa artesanal de joyería y de otras cosas utilizando las conchas de abulón de su granja de abulón.

La comunidad depende en gran medida de la pesca de abulón, y el enorme El Niño, junto con “La Mancha (“The Blob” en Ingles) de 2013-2015 tuvieron un impacto devastador. Para los que no lo saben, el Niño es un ciclo climático que ocurre cada 2-5 años que afecta las pautas atmosféricas mundiales. Hace cinco años, el Niño fue uno de los más grandes que se ha registrado y la enorme cantidad de agua tibia acumulada en la costa del Pacífico destruyó muchas cosas en su camino. La pesca de caracoles y abulón en la Isla Natividad colapsó totalmente con este evento debido a la combinación de estos tres factores agravantes:

Arturo muy feliz

Aprendiendo sobre dos diferentes especies locales de Abulón. (Haliotis corrugata, Haliotis fulgens)

Este laboratorio es en donde traen el abulón para obtener la talla adecuada

1) El agua cálida resulta en que menos algas sean capaces de sobrevivir y por lo tanto una disminución de la comida y el refugio mecánico.

2) El agua cálida y la pérdida de refugio contra las algas resulta desfavorable para que las larvas planctónicas se establezcan exitosamente como juveniles

3) Las áreas que aumentan la infiltración de agua cálida y periodos de tiempo de anoxia conducen a una menor supervivencia

El cineasta Gustavo M. Ballesté realizó un breve documental sobre este evento, el documental ilustra bellamente los matices y las diversas consecuencias de nuestro clima cambiante. A partir de este evento la comunidad se ha adaptado y, mediante esta estrategia y el estricto gobierno autónomo de las prácticas pesqueras, están viendo la recuperación en apenas 3 años. Sin embargo, la comunidad está muy consciente de que los niveles históricos nunca más se volverán a ver, y que las prácticas necesitan cambiar permanentemente para que este recurso siga manteniendo a sus comunidades. Un artículo de los afiliados de COBI en Stanford descubrió que frente a una creciente incertidumbre de recursos, los usuarios de recursos eligen reducir la cosecha para compensar la futura disminución.

Para mí, esta es una conclusión esperanzadora. En estos tiempos de crisis, muchas veces me siento deprimida por aquellos que no quieren ver la realidad. Baja California es un lugar hermoso y loco donde el desierto se encuentra con el mar. Cuando el ambiente terrestre es tan severo, la gente se tiene que confiar en el mar. La pesca forma una parte importante de la economía aquí, y queda muy claro que las comunidades están trabajando juntas para adaptarse y mitigar los efectos del cambio climático, el cual que repercute directamente en la vida y los medios de sustento de la gente. Lo que creo que hace a este sistema tan único es que las pesquerías son en gran parte autogobernadas, y los pescadores son buceadores así que pueden ver y entender los cambios que ocurren a su alrededor. Por esta razón, organizaciones como COBI son vitales para proporcionar conocimiento de nuevas técnicas y datos con el fin de ayudar a las cooperativas a adoptar nuevas prácticas. Afortunadamente aquí en la península de Baja California las cooperativas pesqueras están dispuestas a aprender y a cambiar sus prácticas para poder preservar los recursos que son tan importantes para su supervivencia.

¡Gracias a COBI y a todos mis patrocinadores por dejarme visitar estas increíbles comunidades!

Gracias a Rachael Stronach, Natalia Carrera, and Alondra Moraan por ayuda con Traducir.