A couple years ago, shortly after graduating I moved to Malawi, Africa to work for a small-scale monitoring program, looking at fish diversity and fisheries in a community on the coast of Lake Malawi. This was an extremely eye-opening moment in my life. I saw so many things I had been taught were unsustainable, yet because of the needs of the local community they were deemed necessary! I realized that conservation is so complex and local involvement and investment is a necessity for success. Because of this, one of my goals for this year was to learn about conservation strategies and marine protection in places where the available infrastructure and social challenges are vastly different than those in North America

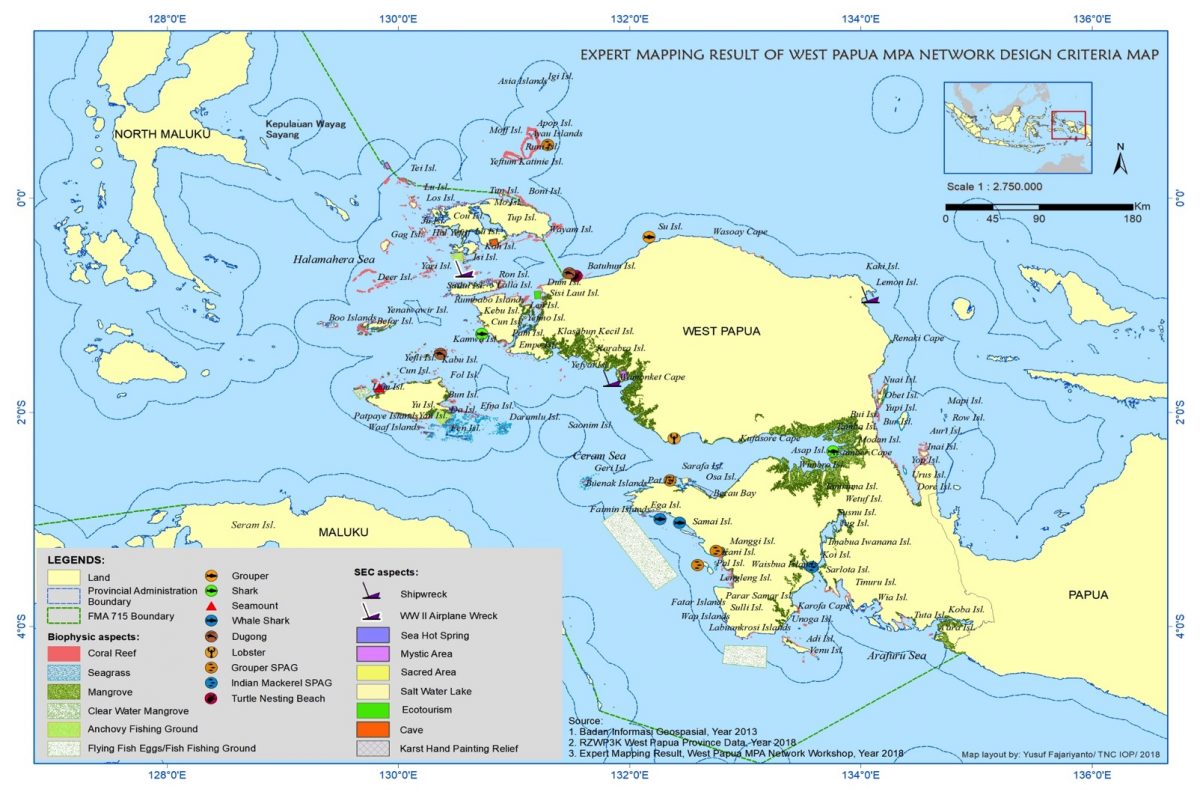

When I shared this goal with my coordinators, they all directed me to Dr. Stacey Tighe, the 1980 North American Rolex Scholar, who for the last 20 years has been consulting with development agencies like US AID in Indonesia and SE Asia on the specific management needs of their Marine Protected Areas (MPAs). As an Island Nation with more than 16,000 islands and with programs that have managed to protect almost 20% of their waters in some form, Indonesia is an extremely complex system. Stacey works in marine conservation in remote areas, specifically in the development of MPAs and MPA networks. This means that through increased application of science they design and build connectivity between MPAs so that targeted conservation goals can be met. She helps with strategic planning, strengthening existing marine organizations, and with training and capacity building. Through this she has forged numerous connections in Indonesia’s many MPAs, and their agencies and supporting NGOs.

To see some of these people in action, Stacey and I went to Raja Ampat, one of the more mature Indonesian MPAs that has a colourful history. Raja Ampat lies on the westernmost tip of West Papua, and is the center of marine biodiversity in the coral triangle and the world. The Papuan culture is very distinct from many of the other island cultures of the nation as it has been isolated from development until recently. The province is also very rich in every kind of resource you can think of, be it oil, wood, fish, or gold. Because of these two factors, as you can imagine, the region was taken advantage of by the monetarily richer and more powerful islands of the country. Due to this conflict, West Papua has gained a special autonomy in governance that has resulted in a more empowered local management. The remoteness and the abundance of the different tiny islands and communities here means that trying to manage everything in a uniform way is futile, so instead the local communities manage themselves through “Adat”. The village Adat is the customary or religious leader of the community; they have authority over ceremonies, weddings and use of natural resources. They technically have equal power to the local leader who works with the government.

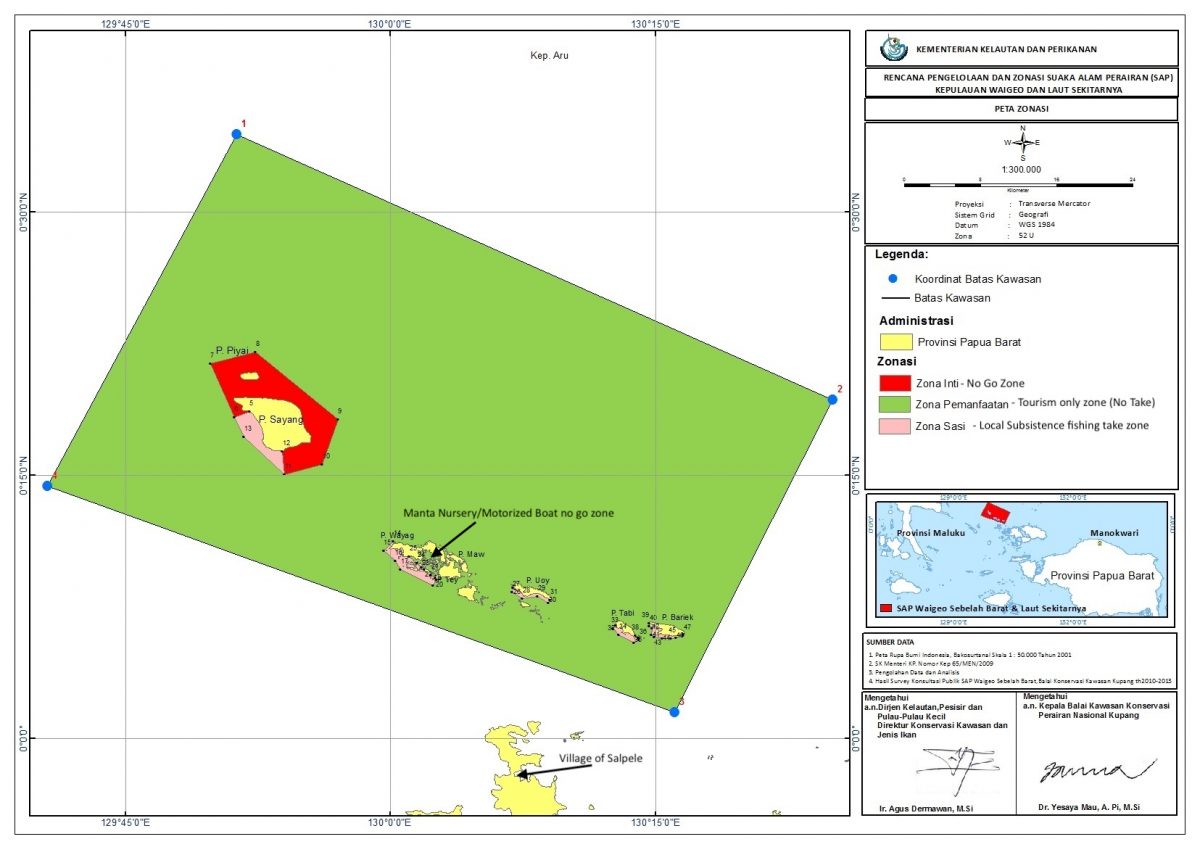

One example where the Raja Ampat National Marine Park has provided exclusive rights to the Adat system for the management of their resources is in the Village of Salpele in West Waigeo. A couple of years ago a new Manta nursery was identified here, so scientists and managers decided that it should be a No-Go zone for all motorized boats. The National Park negotiated with the citizens of Salpele so that they will be the sole provider of canoes and guides for the visitors to the Area. This is beneficial for the community, the national park, and of course the Mantas. However, there are many places and situations where the Adat system doesn’t work so well, and community and management cooperation is much more difficult to come by.

In order to learn more about these challenges, Stacey and I first stopped at the port town of Waisai to meet with The Baden Kawasan Konservasi Perairan Nasional (BKKPN) or National Agency of Marine Protected Areas and the provincial Department for Marine and Fisheries Raja Ampat agency (BLUD). They met us at the airport and immediately took us out on a half-day marine patrol in the area. We visited two ranger stations, one of which was the famous Manta Cleaning station; Manta Sandy. This isolated hut built over water near the dive site is manned daily during the high season to try and enforce proper diving etiquette, check for paid entrance fees to Raja Ampat and limit numbers of divers on the site in order to reduce stress to the Mantas. (More on this later)

The next day we met with them again for a day of discussion regarding regulation and challenges specific to this area of Raja Ampat. Between the two jurisdictions there are over 1.3 million hectares that have to be monitored and patrolled on a regular basis. This is obviously very costly, and these organizations are small. BKKPN has a total of 8 full time staff! And though BLUD has an 180 person staff, the majority of them are trained community observers who are contractors with minimal training.

BLUD and BKKPN conduct coral monitoring in their respective areas every year in conjunction with NGOs. Frustrating to me, as a scientist is that due to bureaucratic zoning and data right issues, they cannot share raw data, and they do not do surveys outside of the MPAs!! This means that they do not have controls that can clearly demonstrate the effectiveness of their MPAs. However, since these studies have been happening for a long time, the corals in this area are known quite well, and the ecosystem health can be monitored reliably over time, and the final reports are publicly available.

BLUD patrols their territory approximately twice a week, however due to the sheer size of the area, it is very difficult to enforce regulation. The BLUD patrols are for two main purposes.

Fish at the Market in Sorong

Yellowfin Tuna

First, in terms of fisheries, they aim to ensure that there is no illegal fishing going on in their waters. This is a particularly sensitive issue here. Dynamite fishing is a highly unsustainable technique that is widely used around the world. In the neighbouring island of Sulawesi, as well as in surrounding nations such as the Philippines and Thailand, this technique has led to widespread reef destruction and subsequent fishery collapse. This has driven fishermen from these areas to the lightly fished areas of Raja Ampat. It is problematic on two fronts; first, due to Marine Protected Area planning, local communities have agreed to only fish for subsistence within the MPAs, and do not commercially harvest species from the park. So when they see fishers from other communities come and destroy their reefs, and make money off of it, it is often difficult to remember why they should not do this themselves! Also, BLUD is not allowed to board international vessels by law. This means that even if they find a boat dynamite-fishing in the area, they cannot take their equipment, their catch, or take the perpetrators into custody. This obviously makes enforcement very difficult!

The second reason for patrols is to ensure that dive operators and other tourism infrastructures are functioning within their rights, including the collection of the entrance fees for Raja Ampat. To enter the Raja Ampat provincial MPA, all international visitors must pay a 1 million rupiah (~75 USD; locals pay less) park fee for a one-year pass that goes towards running the fisheries management, and to compensate locals for visiting their waters. As there are many points of entry to the park, and as officers cannot board all ships, this is difficult to enforce, and it is easy for local and international visitors to slip through the cracks, costing the parks thousands of dollars every year. Many operators don’t ensure that visitors have the Entry pass before embarking on activities with them, as operators are not required to submit logs of their guests. Even worse, some operators don’t follow the rules for wildlife safety (i.e., diving before the rangers arrive at Manta Sandy, approaching or harassing threatened animals). This lack of cooperation stems from the prioritization of profit that characterizes the worldwide struggle with conservation, a minimal of understanding of the consequences, and the presence of many short-term outside tour operators without deep local ties. In addition, since establishment of BLUD, administration changes have resulted in funds being rerouted in a way that they don’t trickle back to the communities they are supposed to which leads to a decrease in motivation. BLUD has made progress in rebuilding the proper flow of funds, but the gap has left some local operators wary.

To understand this knowledge gap we wanted to visit a local tourism operator, so we went to the tiny Arborek island to dive with Githa at the Arborek dive shop! Githa is an exception to the rule. She is a passionate marine advocate, active member of the community, and the founder of the Kitong Bisa Learning Center; an education center focused on Raja Ampat conservation issues. She also speaks out against other operators she sees violating rules and disrespecting the reefs. We asked her about what she saw as the biggest threat to Raja Ampat.

For her it’s a lack of tourism regulation. For example, during the high season they regularly have over 5 live-aboards off of their coast every night, and more than 50 in the area, despite limits below that. As in many places, dealing with live-aboards and local communities, to distribute benefits is a challenge. As there is no mooring system, many live-aboards anchor on living shallow water reefs causing damage. They also bring their guests onto Arborek and other small islands, often without permission, with no requirements to give anything back to the economy. In such a small community (only 200 people), having so many strangers in the limited space obviously has wide social implications. Secondly, there are few rules regarding diving skills. Raja Ampat is rich in life because it has a huge influx of nutrients brought about by crazy currents. It is not easy diving, and without advanced diving skills and proper buoyancy, causing reef damage is easy! Githa has watched dive sites around her decay over time as tourism continues to increase without matching regulation.

BLUD, BKKP and the tourism board are working very hard on trying to implement a mooring system, and a more balanced live-aboard licensing system as well as other management tools. But the classic lack of funds, and mounds of red tape are making it difficult; in particular, a change in authority for marine waters from the district to the province. This is now being addressed, and some progress is visible. Both Githa and the Parks managers agree that the BKKPN, BLUD, and the tourism sector need to form a cohesive form of co-management to be most effective, and with this year’s new draft provincial Raja Ampat MPA Management Plan there is a push to create this collaboration. In a place as important as Raja Ampat this is vital as we continue to lose global biodiversity at an alarming rate!

I spent nine days on Arborek Island diving with Githa. Serendipitously, I was here at the same time as a small scale Canadian NGO called the Wide Open Projects. A group started by three passionate individuals, their goal is to show that anyone can make a change by taking action! They have been coming to Arborek since 2016 and after a small pilot project last year they came back this year with 4 other likeminded individuals to build coral transplant structures to stabilize reefs in front of Arborek, in conjunction with Githa!

As I mentioned above, and unlike many global reefs, the corals in Raja Ampat are mainly physically damaged, whether by boat hits, anchors or people! Often when shallow reefs are damaged they begin to erode and cause an avalanche of rubble that subsequently damages deeper corals. Working with this group of passionate people was a blast because their goal is always to involve and directly benefit the community. Over our time there we built and deployed over 40 structures with the kids in the community. We developed a monitoring protocol to watch their progress over the coming years and with Githa’s help we will have data to quantify this. The Wide Open Projects team is hoping to grow their initiative to a larger scale and to other communities in the coming years. Check them out, and maybe reach out if you want to do something meaningful in a mind blowing, and important location.

I had a wonderful time in Raja Ampat. As one of the best diving destinations in the world, I feel so lucky to have been able visit and learn about the local perceptions of the place. I was able to see both top down and bottom up conservation strategies through the Parks services and Wide Open Projects respectively. This trip clearly demonstrated to me that as usual, management and conservation are extremely complex issues that require strategies that are specific to the cultural nuances and needs of the area. As a tourist, making the effort to find out where your funds will be going to, and what fees you are supposed to be paying can really help! Choose the options that give to the communities with the fewest degrees of freedom, and maybe opt out of activities that may not be the best for the environment we are trying to protect.

Thank you to Stacey Tighe, BKKPN, BLUD, Arborek Dive Shop, and Wide Open Projects for being great hosts. And of course thank you to my sponsors Reef Photo and Video, Nauticam, Aqualung, and Fourth Element, and to Rolex and OWUSS for making this happen!