Like the scholars who have come before me, it is an honor to achieve such a unique, prestigious, and competitive award like the Rolex Scholarship. It honestly feels like you won the lottery. However, as the first African American to receive the OWUSS Rolex Scholarship in almost 50 years since the award’s inception in 1973, it musters a whole new range of feelings that carry a weight all their own. When I got the call letting me know that I was selected, I knew it was more than just a win for me, but a win for others that look like me, too. Most important, though, it was a sign of hope. It was hope for the future generations to come in the wake of witnessing unjust deaths over and over again like George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, Ahmaud Arbery, Elijah McClain, and countless others. To every black boy and girl, it is a well-known fact that throughout the centuries, people of color, especially black people, have been marginalized, discredited, and denied the opportunity to pursue their dreams. Sadly, many of these toxic ideas are still prevalent within American society today. Still, it is because of the African Americans before me, like the Tuskegee Airmen who stood and fought for our right to simply be treated as humans, that allowed for others like me to be where I am today and to continue spreading hope. In part, I owe all my successes to them. That is why, when I heard about an upcoming project to excavate a Tuskegee Airmen’s recently discovered sunken plane, I knew it was something I had to participate in during my scholarship year.

The Tuskegee Airmen

I had actually first heard about the opportunity a few months before my Scholarship year started. As a member of the National Association of Black Scuba Divers (NABS)and MASK which is the Midwest regional group associated with NABS, I was privy to a lot of group chatter about the sunken airman plane in Michigan and the plans being drawn to excavate the pieces of it. The project was spearheaded by the Michigan Department of Natural Resources archeologist, Wayne Lusardi and was additionally supported by NABS and Diving with a Purpose (DWP). As part of the Midwest group of NABS, I was invited to participate in the excavation of the plane and of course, knowing that this was going to be an extremely important event culturally and personally for me to be involved in, I couldn’t help but to accept. It was one of the first things on my scholarship calendar. However, the project wouldn’t get started until August.

Once August came around and after keeping in regular contact with Wayne, we had planned my visit for the last week of the excavation which landed right when I would be leaving Monterey Bay. When the time finally came, I flew into Detroit, Michigan, and ended up rendezvousing there with the amazing Brian Smith and later the fun and lovable Andrea Williams, both of whom I had met in Egypt in 2019 during the NABS annual summit. Brian, who is a fellow NABS and MASK member, also worked as the curator for the Tuskegee Airmen National Historical Museum in Detroit and directs a rocket, drone and flying program for young minorities. As such, he was extremely dedicated to the project and gladly told me all about his gathered history of the Tuskegee Airmen. The next day we picked up Andrea Williams, who currently serves as the Vice President of NABS and works at a dive shop in Maryland, and she was also really excited to be there. It was good to see them again.

Brian Smith

Since the site was about an hour away and the boats for the excavations only left in the morning and weren’t back until late anyway, Andrea, Brian, and I instead spent our first day in the city of Detroit and had a blast. The downtown area was more beautiful than I originally imagined and, in many ways, reminded me of home. As I looked around, I thought it was funny that despite all my travels, I had never ventured there before even though it’s practically next door to Ohio.

Downtown Detroit

While we were there Brian showed us around the hangars where they keep old plane models and aircraft as well as the artifacts that were being procured for the new museum. It was amazing to see all the different planes and learn the history behind some of them. It was also pretty cool to see some of the artifacts that had already been collected from the site and to get a preview of what we would be seeing. Later that day we also got to go to the old Tuskegee Airman exhibit to look around as well as see Brian teaching some students how to launch a rocket, which made my soul warm. It was such a cool and fun time.

Looking at the planes in the hangar

That afternoon we drove to the site where we met up with Wayne, his son Nick, and Hunter Whitehead of Coastal Environments Incorporated. It was nice to finally meet Wayne in person. As the evening fell over us, I quickly discovered who were the night owls alongside me. Once 10:00 pm hit, Wayne and Nick and I were the last ones left standing. While we burned the midnight oil, I asked Wayne more about the background of the project and he was happy to tell me everything.

I learned that the aircraft we were excavating was a Bell P39Q AirCobra built in 1942 and belonged to an airman named Frank Moody. These planes were built in Buffalo, NY for the United States Army during WW2. Built with the war in mind, the fighter plane boasted three cannons, a back engine, side doors, and the first tricycle landing gear; however, the planes were quickly replaced with newer models and relegated for training in Shatford Field, MI. In an almost similar fashion when the Tuskegee program was started in 1941, due to the army’s fear of integration, black recruits were also relegated to training in Tuskegee, Alabama. While it was meant to be a slight against black pilots, it ended up being an advantage because while white pilots were trained for only a few months before entering combat, the Tuskegee Airmen had had at least one or two years of training before they finally entered the war in 1943 as the 99th fighter squadron and amazed the world with their flight skills. However, once the 99th squadron was deployed, the advanced trainings were dispersed to different parts of the country and all of the fighter pilots were moved to Michigan where they were stationed for only a year. During that time Lieutenant Frank Moody, who was born in Oklahoma but raised in Los Angeles, was stationed in MI for advanced training after graduating as an aviation cadet in Tuskegee. Moody was assigned the P39 and on April 11th, 1944, during a gunnery training over Lake Huron, what appeared to be an inflight malfunction with one of the cannons, the plane lurched and eventually led to Moody’s crash. With no canopy exit and flying at what was assumed to be about 200 mph only 100 feet above the water, the crash most likely killed him on impact. Two and a half months later, Moody’s body was found miles away from the crash. The coast guard and army searched for the craft but to no avail. 70 years later to the day, a dive charter run by David Losinski and his son Drew found parts of the remains. The Michigan Department of Natural Resources was called and then NABS, DWP and the Tuskegee Airmen Museum were called, too, and the rest is history. I thanked Wayne for all the info before we finally headed off to bed. Now that I knew all the details and the history of the project, I was more than excited to get started.

Every morning from then on, we headed out on the boats which were being run by the state patrol, sailed our way out to the various sites, and did about three or more dives a day. Lake Huron was amazingly nice to dive in. When we jumped in the water the temperature was always in the high seventies, with great visibility and a maximum depth of 30 to 40 ft. Once we got down, we collected anything we could find and bring up. Other items that were too big, like one of the wings itself, were tagged and attached with a buoy so that we would know where they were and could find them later.

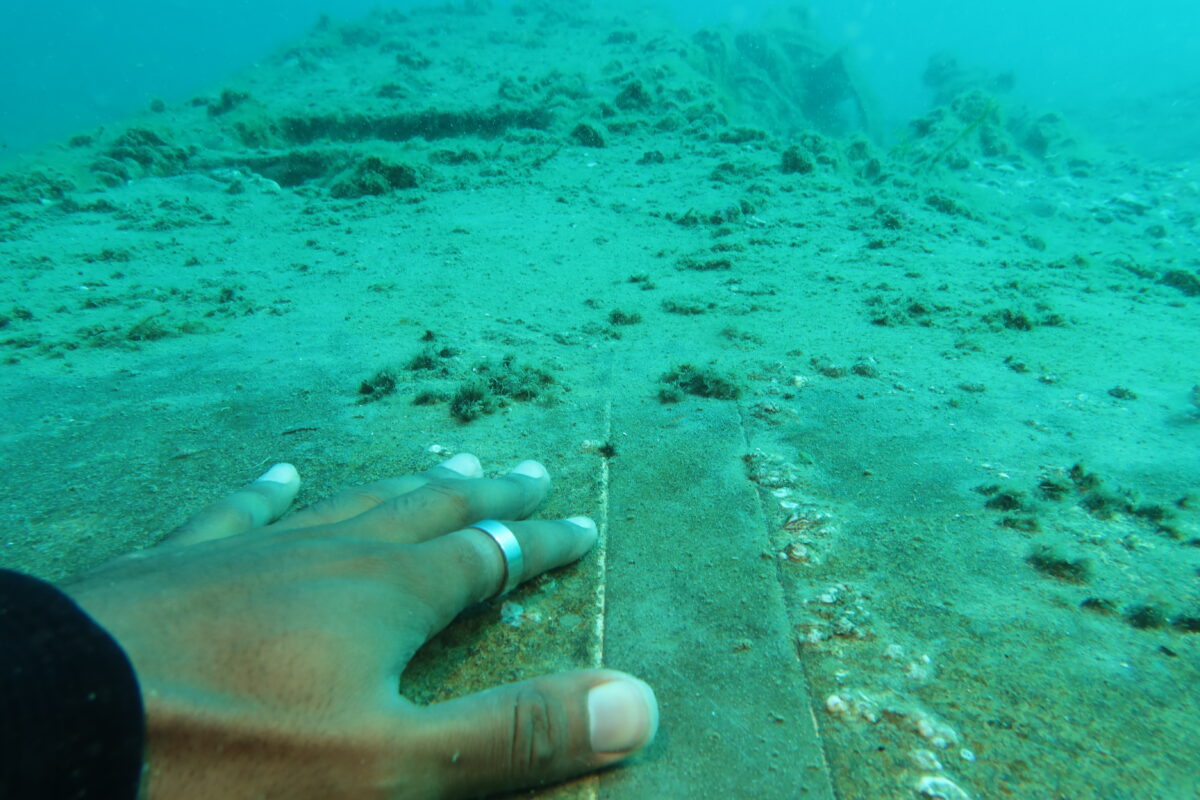

One part of the wing

I remember the first dive we did; I was so excited to help tag one of the three cannons we had found! To find things at each site, we moved using a survey tape measure and did circular sweeps to cover the ground. We found several pieces of shrapnel and armored plates. Though it wasn’t much at first, I was so enthralled that if someone had told me that I was the next Tomb Raider or Indiana Jones I would have believed them.

Some of the artifacts we found

We got to meet and eat with the father and son duo, the Losinski’s, who had actually found parts of the wreck and discovered who it originally belonged to. While being filmed, we talked with them and got an inside scoop as to how they came upon their discovery, which I thought was pretty neat. Of course, we additionally got interviewed ourselves as members of NABS, and me as a part of both NABS and the OWUSS Scholarship about what this discovery really meant to us.

Having a touching moment with my history

While we were out in the field, I also got to work with Andrea to obtain my underwater navigation certification. I was so proud of myself for some of the feats I accomplished. At one point we had accidentally left a small artifact on the lake bottom and as the last one to get back on the boat with all my dive gear still connected and the most air left, I offered to take a quick look before we had to leave. So, I jumped back into the water and using the landscape around me, remembered exactly where we had left the tiny artifact. When I returned to the surface with the piece in hand, I felt a strong sense of accomplishment and proudly presented the artifact to the rest of the team who were just as impressed. It was a cool moment.

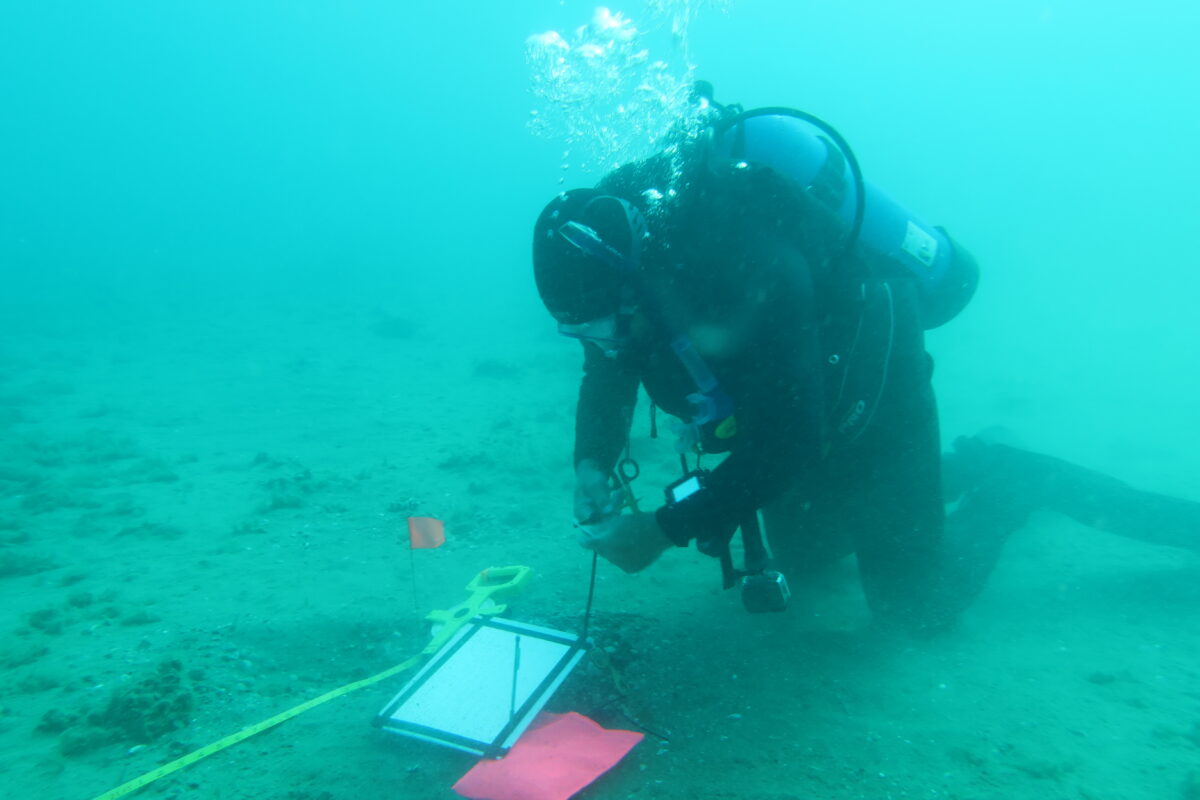

One of the coolest moments I remember, though, was when some of the state patrol officers were able to help us with metal detectors. Once they used those, more than a hundred artifacts were discovered. It was amazing how many objects were found. As soon as you ducked your head underwater you could see all the newly discovered items. Bullets, shell casings, wiring, you name it. There was almost too much. However, since it was close to our last day of diving, in good archeological practice Wayne suggested we use trilateration to know how each artifact was oriented in the water. At this, I was completely lost. What the heck was trilateration and how did it work? In short terms, trilateration is a method of surveying in which the lengths of the sides of a triangle are measured. Though it can sometimes be done electronically, too, we were going to be doing this by hand and it was going to be important to get the orientation and all the correct measurements quickly. At first, Wayne had the only the divers that knew how to do it go and I just got to tag along but once my dive buddy started having ear troubles, we had to surface. Once we were topside again, I asked my buddy to instead teach me. After some hesitation, he told me everything I needed to know before I gathered all the materials that I would need and went down to do it on my own. I was really nervous that I would miss something or that I was doing something wrong but I did my best. I did trilateration, artifact after artifact and when I finally came up I showed my work to Wayne to make sure that I was doing things right. He looked over my notes and praised my quick thinking. To my relief, I had done everything correctly and understandably. Phew!

Doing underwater trilateration for the first time

Our very last dives were very special as we got to bring up all of the cannons. Since I had been able to bring up one of the cannons before, this time I stayed topside on the boat and for the first time got to use my drone out in the field to film the event. It was a proud moment and one that ended our dives on a strong note.

Bringing up the three cannons

Once we returned to base, we cleaned up all of our stuff and got ready for the next day. Even though the diving part was over, there was still a panel discussion and a ceremony that would be happening in the next few days. Wearing what few nice clothes I had with me, Brian, Andrea and I rode out to the panel where Brian, Wayne, and two others were interviewed by an old friend of mine who I had also met in Egypt, Ayana Omilade Flewellen! Later the next day I also got to see my friend and role model, Justin Dunnavant at the ceremony where they unveiled a monument dedicated to the Tuskegee Airmen and the sacrifices that they made for the rest of us. It was a really powerful moment. We then ate dinner and there Ayana gave a beautiful speech about just that: sacrifice, and how it shaped not only the Tuskegee Airmen’s lives, but ours as well.

What a beautiful ceremony

Once the ceremony was over, I thought to myself how important it is for the stories of those who came before us, like Frank’s, to be uncovered and told because they inspire us and at the end of the day they really allow us to appreciate all that we have accomplished thus far in spite of everything. For me, one of my biggest goals during my scholarship year has been to expand diversity in the world of underwater diving, foster more diverse collaborative innovations, disrupt damaging stereotypes, and to increase minority exposure to unique educational diving experiences. However, I think the most important thing I can do by telling my own story and bringing to light all of my own challenges, blunders, and triumphs during my adventures, is to give back to my community the same thing that those Tuskegee airmen gave me and so many others…

Hope.