My name is Rosie and I am the 2022 North American OWUSS Scholar. I grew up inland Canada and developed a passion for marine science at a young age. I set my sights on pursuing a career in the field and went to study Biology and Environmental Studies at the University of Victoria. During my studies, I worked as a dive instructor, underwater photographer and in a variety of conservation jobs. When I got selected for the OWUSS scholarship, I recognized this as a dream opportunity to learn about marine conservation on a global scale. Through this scholarship, I plan to explore the fields of fisheries management, Marine Protected Area (MPA) development, and community engagement. I plan to use the OWUSS scholarship year to gather the most effective tools I can to pursue a career in ocean conservation.

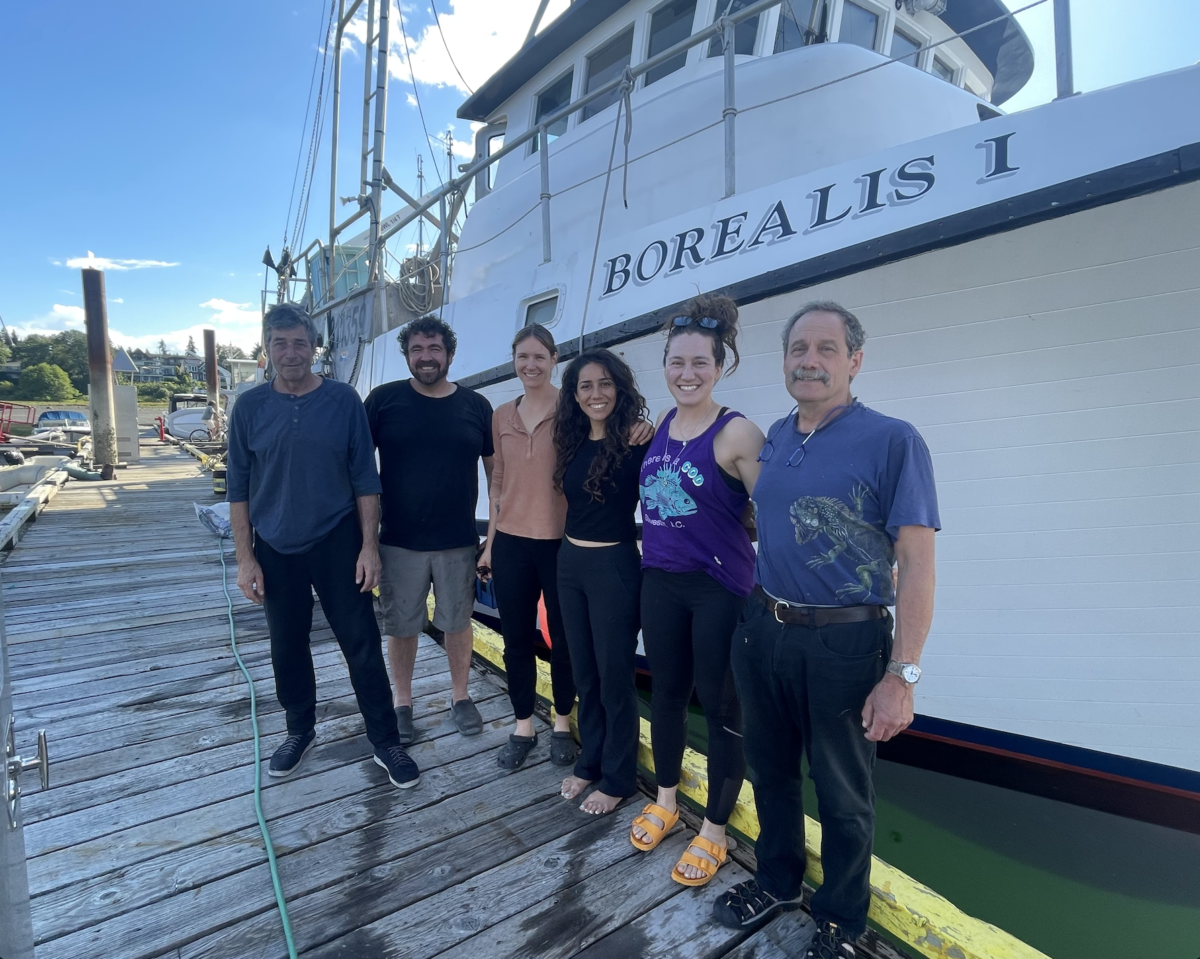

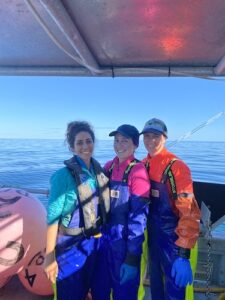

This vision took me to my first scholarship opportunity of learning about sustainable fisheries firsthand in the Pacific Northwest of Canada. Stale crackers, hard work, bad weather, endless rain, rough words and rougher waves was what I braced myself for as I prepared for my stint on a commercial halibut fishing vessel off the west coast of British Columbia (BC). Hard work I did find, but the rest of my expectations faded as I was introduced to Tiare and her fishing family aboard the Borealis 1. Their work utilized a different mindset when it came to fishing. They were fueled by an endless stream of encouraging words towards each other as they spent the long summer days setting and hauling gear, pulling halibut after halibut off the line and storing them in the boat’s large storage hold, congratulating each other enthusiastically any time someone pulled up a particularly spectacular fish.

Tiare’s family was endlesly kind and supportive to me and to each other throughout the trip, teasing lightly and loving deeply. They were a joy to be with. Tiare told me from day one, “We fish a little differently… ours is family fun fishing. We even have a book club and you’re welcome to join. This year’s book is about faeries.” Her cousins chimed in to encourage me to read the book series too. I held off for two days, determined to read a book about fishing and fully immerse myself in the fishing experience. When I countered their encouragement with this argument, they firmly let me know that the only way to truly immerse myself in the fishing experience was to join in the book club with them. I finally gave in as they put the book right in front of me with a meaningful stare. So we fished during the day, joined by a multitude of sea creatures including puffins, albatross, whales, porpoises, fur seals and mola mola and by night we launched ourselves into the fantastical worlds of faeries in our reading. During the long sets and hauls we would share our thoughts about the books and gossip about all the characters.

We had set out for our trip late on a Saturday evening for the northernmost point of Vancouver Island to begin our 10 days of fishing. Tiare warned me to take seasickness medication just in case the rough rolling seas of the open ocean were to turn my stomach into an unfortunate mess. Our first day of fishing, we faced light mist and rain and some rolling seas. As my fingers turned numb poking icy bait onto hundreds of fish hooks, I prepared for what I thought would be 10 days of cold, rainy, foggy weather. I asked Dave, our captain and Tiare’s father, if they ever get glass calm seas when fishing in the open ocean and he said never. It doesn’t happen. Yet the next morning when we woke up to bait and set our lines, there it was. A glass calm sea. We all felt like we were on borrowed time as we savored the sunny weather and calm ocean, thinking it would not last. By the fifth day of perfect weather and hardly a wave, Dave came up to me and said “I’m sorry I lied to you”. “About what?” I asked, surprised, already forgetting our conversation from before. “When I said we never get glass calm seas,” he responded as we both laughed. The weather really felt surreal. Our fishing days started early, at 5:30am with setting the lines. After morning sets, the crew rested until after lunch when we would haul gear until well past 9pm. The crew pulled each fish individually onto the deck and returned the ones that were undersized or not on the license to catch, alive back into the sea. The long days of hauling and preparing fish would have everyone’s hands and shoulders sore by nightfall.

In the nights after we finished hauling we ate delicious home cooked food made in the boat’s small galley as we enjoyed the 10pm sunsets that graced us in the most northern parts of BC during the endless long summer nights. I was caught off guard at the incredible meals of lasagna and roasts, shepherds pie and salads. Far better food than I would have cooked for myself at home as I laughingly admitted to the team that I was fully expecting to eat canned soup and crackers for 10 days straight. They informed me that they liked to eat well when working hard, that it made the work more enjoyable. I couldn’t agree more. As we fished, we passed places and islands I had only read about when I was completing my undergrad at the University of Victoria. We passed the Scott’s islands, a newly established National Wildlife Area that acts as a seabird sanctuary. Later we passed Gwaii Haanas National Park Preserve, an important cultural and ecological area in Haida Gwaii island chain. I was in awe of being able to see these places with my own eyes. Beautiful location aside, I had wanted to come on this trip so that I could learn more about marine resource management and in particular, fisheries management. It felt fitting to learn from doing and experiencing. Tiare had invited me to come aboard her family’s fishing boat through a previous North American Rolex Scholar, Neha Acharya-Patel. Tiare had grown up fishing with her family and had studied coastal marine resource management in Iceland. Her family championed sustainable fishing and worked to improve the management of fisheries up and down the BC coast, contributing to data collection and management strategy meetings.

I was so excited to have this opportunity to come aboard the boat and participate in a commercial fishing trip, knowing that I would have 10 days to pepper them with all my fisheries related questions with no phone service to distract us. The family’s enthusiasm for what they do and their love for the coast was infectious. Tiare’s outlook on conservation and fisheries management was insightful and inclusive; she never looked down on those who held opposing opinions. She valued all points of view in the conversation of management and sought only to improve the industry and the world that she cares so deeply about. Tiare’s father, Dave, who has spent over 40 years in the fishing industry shared openly about fishing management up and down the coast. He taught me about the Quota system, and how the introduction of the individual transferable quota system (catch share) ensured that they had no bycatch when fishing for halibut. Their boat held a halibut license and allowed them a certain quota of halibut each year, which also included quota allocated to certain fish that were likely brought up as bycatch. This extra quota allowed them to keep other fish caught on the line such as black cod, lingcod and a variety of species of rockfish. The counts of each of these fish were included in the total allowable quota for each of these species per year in BC such that bycatch would not result in overfishing or food waste. No fish went unaccounted for. Cameras mounted on the boat stabilizers captured footage of every fish brought on board. These cameras were audited by a third party service to ensure that beyond their own personal reporting, each boat was being externally monitored to ensure their compliance with fisheries regulations. All undersized fish were released as they came up the line. Theirs was a fishery essentially with no bycatch as everything covered under their quota system was hauled on board and anything that couldn’t be kept was returned to the ocean with very low mortality rates. I was impressed by the extent of management. It was beyond anything I had expected. There were even mechanisms and tools used to deter seabirds from taking bait and thus getting stuck on the line. Tiare’s family used two different deterrent methods, including trailing buoy lines and a water cannon, both of which kept albatross and other seabirds from nearing the boat. I learned a great deal during my time with Tiare and her family. Aboard their boat, I was taught all the aspects of fishing halibut, from setting lines to hauling gear and fish, to gutting for storage, to rotating sites, reducing bycatch and politics of fishing. Through our daily conversations they patiently answered all of my questions about quotas and management strategies and the history of fishing up and down the coast. They welcomed me into their fishing family and shared openly. They gave me a beautiful perspective of what effective resource management can look like and how fisheries can be managed sustainably. Not all fisheries are managed in this manner. There are many negative stories about fisheries and it is encouraging to see fisheries managed as they should be, with monitoring and accountability and a mindset that ensures there will be enough fish and resources for future years. It is our task to ensure that all fisheries are managed in this way.

I look forward to continuing my year with a greater understanding of marine management from fishing to conservation. I will take the lessons learned from this experience with me throughout the rest of year. A huge thank you to Rolex, Our-World Underwater Scholarship Society, DAN, and my product sponsors Aqua Lung, Diving Unlimited International (DUI), Fourth Element, Halcyon, Light and Motion, Nauticam and Reef Photo and Video for making these opportunities possible. I am looking forward to where the rest of the year will take me.