Hello from South Florida! I am here in the Florida Keys diving with one of the pioneers of Underwater archaeology, Charlie Beeker, and a group of his students training with the Underwater Science program at Indiana University. Charlie founded the program in 1992, and has been training students, and working on the preservation of subtidal biological and cultural resources since .

I met Charlie, and Indiana University’s current Diving Safety Officer Sam Haskell at the Scholarship Society’s annual weekend in New York City in April 2019. They were super friendly, and immediately invited me to participate in their work. So I came down to the Florida Keys, where Charlie has been integral in creating a conservation plan for many of the iconic ship wrecks in the area.

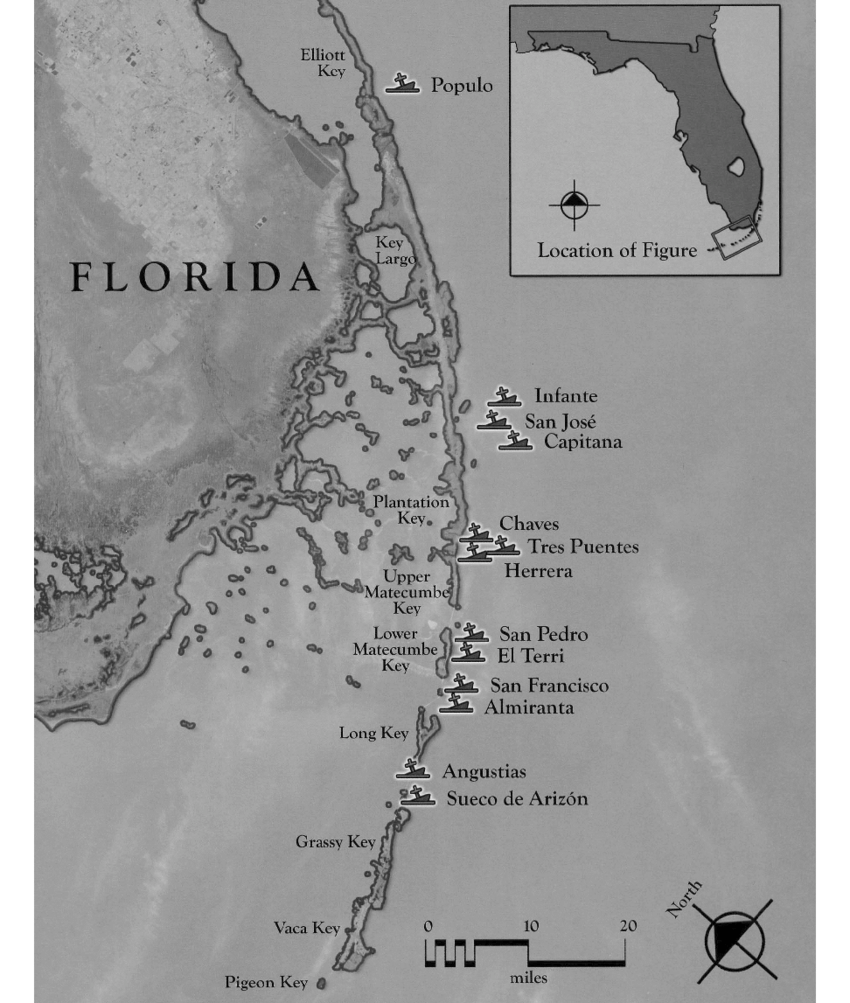

Two of the most interesting of these are the San Pedro and the San Felipe. Back in 1733, a Spanish fleet consisting of 5 Galleons, and 13 Merchant ships left Havana, Cuba on the arduous journey back to their home carrying treasures pillaged from the New World. However, odds were not in their favor and after hitting a hurricane, the fleet was scattered across 80 miles of the south Floridian coastline. At least one ship made it back to Havana, but the exact number of survivors is not known. These ships now make up some of the oldest artificial reefs in North America.

Back in the 1960s when recreational scuba diving was taking off, and all of the Spanish treasure hiding on the many wrecks off of the Florida Keys became accessible, salvage diving took off! Without any regulation, in just a decade or so, many salvage divers found their weight, if not more, in artifacts, but at the cost of all the archaeological context that these shipwrecks had retained for centuries! Only in 1977 the did State of Florida’s underwater archaeological research section do a primary survey, and then a decade later they affiliated with Indiana University to create legislation for the Abandoned shipwreck act of 1988, that stopped treasure hunting and created a plan for their protection. The next year, through Charlie’s persistence, the San Pedro, one of the heavily salvaged Spanish Galleons, became the San Pedro Archaeological reserve. Charlie’s goal was to create an integrated system that would not only conserve the historical importance of the sites, but their associated biodiversity as well. His idea was to create Marine Protected Areas that were Living Museums of the Sea.

Sheltering fish at the City of Washington

Archway on City of Washington

Invertebrates covering remains of the City of Washington

“The establishment of Marine Protected Areas (MPA’s) is the most effective way of preserving submerged cultural and biological resources for the future. Properly designed, interpreted and managed, MPA’s not only protect resources, but also play a vital role in educating the current generations about their historical past and environmental present and can be used as a tool to further economic development (Hanselmann and Beeker, 2008)”

As we all know, conservation requires an economic value for it to be considered worthwhile within our system. Charlie demonstrated that the conservation of these sites was much more valuable than their pillaging.

Charlie admiring the Exposed wood on the San Felipe

Charlie and Sam examining Galley bricks on the San Pedro

In sites that were already heavily salvaged, like the San Pedro, Charlie and his team sometimes add replica artifacts that had already been removed to return some of the magnificence, and sense of cultural value. In 1989 they added 7 cannons surrounding the heavily salvaged pile of ballast stones that is all that marks the fate of the legendary Galleon. 2019 marks the 30 year anniversary of this event and so we were tasked with surveying the archaeological and biological components of the site and its Sister ship the San Felipe.

Both the San Pedro and the San Felipe went down in that deadly hurricane in 1733. However, because the San Felipe did not yield any treasure in its initial salvage, its ballast pile remains relatively intact, in fact it is probably one of the most intact wrecks from that time period! In hindsight, it was found that the San Felipe was in fact a British owned merchant ship that was not holding any treasure. Due to the differences between the two ships, a comparative survey is of interest, and this was where IU’s Underwater Science program came into play.

Lobsters hiding in the ballast stones

Spotted Moray on the San Pedro

Growth and Life on the San Felipe

Though the main purpose of the trip was to survey the wrecks, this was only accomplished through the Underwater Resource Management class that the IU Underwater Science program offers. I joined a group of inspiring students training in science diving techniques to collect the data that will be used to report the biological and historical state of the wrecks. Sam Haskell, IU’s DSO, and Kirsten Hawley, the Underwater Science lab coordinator, were responsible for the dive training and survey techniques. On each ship, we inventoried ballast piles, fish, corals and invertebrates, and also mapped site features like plaques and mooring blocks. On the San Pedro the cannon locations were mapped and relocated, and on the San Felipe, we photographed the crazy dark original wood of the ship that had been uncovered by the 2017 Hurricane Irma.

Charlie’s lab was one of the first to start employing 3D photogrammetry to survey subtidally, and so after a little practice, I was able help create the 2019 model of the San Pedro! Look at it here. 3D photogrammetry is a technique that uses many overlapping 2D images to create a 3D model of a subject of interest. It allows the lab to compare sites over a temporal scale, as well as allowing them to take precise measurements in the lab.

We had an amazing week doing this work, as well as diving on many wrecks other than the Galleons, like the “City of Washington” sunk in 1917, the “Benwood” sunk in 1942, and “Spiegel Grove” sunk in 2002. Each was totally different, and covered with life! I had never considered how archaeological significance could be interpreted hand in hand with biological significance, and it was incredible to witness. I want to thank the IU Underwater science program for being so welcoming, and for teaching me so much!