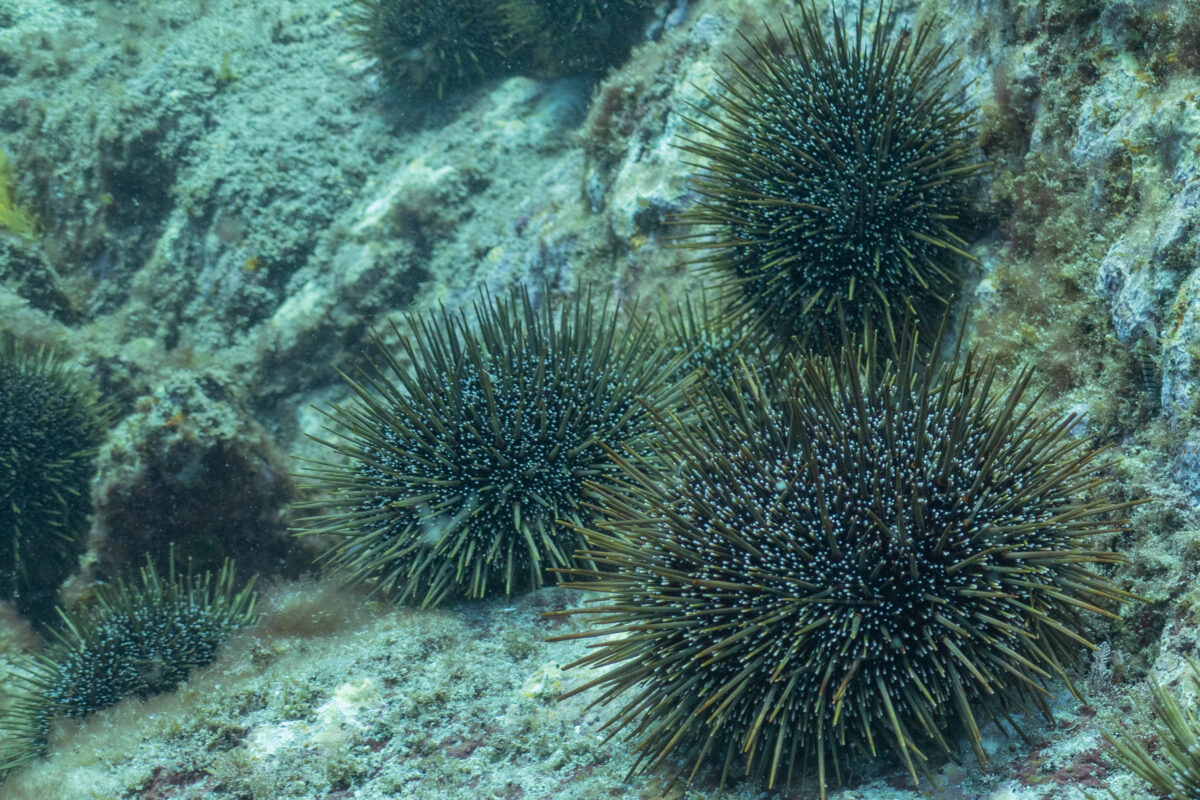

Aotearoa New Zealand is a biodiversity hotspot, home to over 80,000 species found nowhere else on Earth. The golden kelp forests found in the island’s coastal waters are under threat from an overpopulation of kina (the M?ori word for this native sea urchin, Evechinus chloroticus), which graze on kelp. Overgrazing turns the kelp forest into “kina barrens”, where essentially only bare rock and kina remain.

For the past four years, Dr. Kelsey Miller has been working on kelp forest restoration through kina removals in northeastern Aotearoa as a part of the Shears Lab at the University of Auckland. I had the incredible opportunity to experience the impact of these efforts when I joined the lab for fieldwork at the restoration sites. I stayed at Leigh Marine Lab, a University of Auckland research facility located next to Goat Island/Te H?were-a-Maki, the country’s first marine reserve, established in 1975. Fishing is prohibited in the reserve, so there is an abundance of fish. Exploring this site was an excellent contrast between areas with and without protections, highlighting the importance of long-term protection and conservation. I also visited the Goat Island Marine Discovery Centre, where I learned about the history of the reserve.

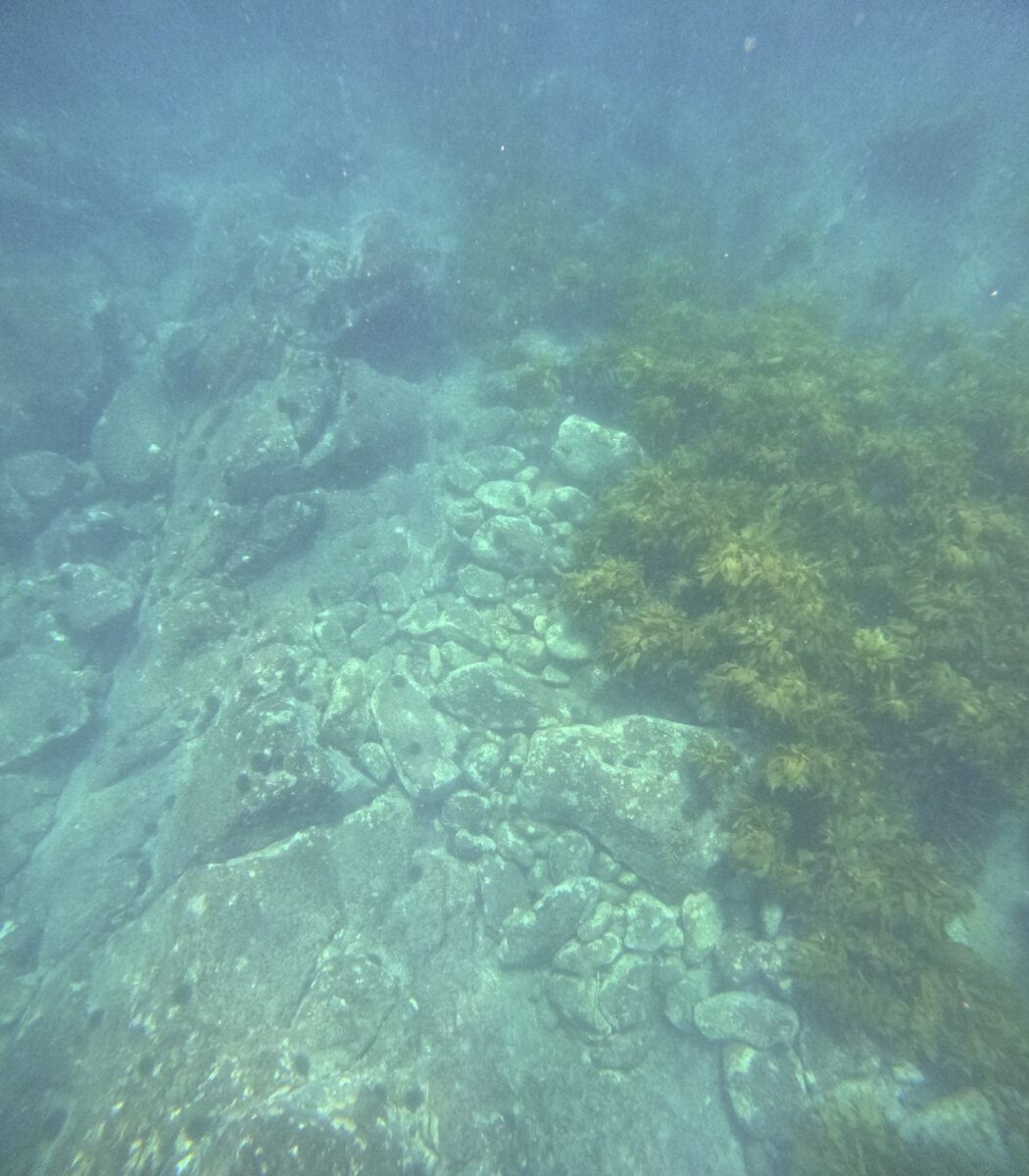

On Hauturu-o-Toi (Little Barrier Island), I saw firsthand an area that had shifted from kelp forest to urchin barren. The difference between the restored and unrestored areas was stark. Kelsey observed that barren patches were starting to form, which had not been observed during surveys the previous year. Even though it had been four years since kina removal, there was a clear difference between the restoration (right side of photo) and control, no removal area (left side of photo).

The increase in barren patches at the restoration sites shows that while removal efforts are impactful, they must be paired with broader ecosystem management. A primary driver of kina barrens is the overfishing of kina’s natural predators, including spiny lobster/crayfish (k?ura, Jasus edwardsii) and Australasian snapper (t?mure, Chrysophrys auratus). Without these predators, kina populations are left unchecked, leading to further kelp degradation. It is important to understand that kina are not the issue or the enemy, but in fact a vital, native part of the ecosystem, and highly culturally important. Kina is regarded as a taonga (treasure) in M?ori culture and has been harvested for centuries.

I also got to join in on fieldwork for the rest of the team, which included sampling for kelp microbial communities, looking at barren growth, and using drone imagery to identify kelp and barren cover. It was interesting to see the different projects and work with different members of the lab. In addition to joining the lab for fieldwork, I also had the opportunity to take part in a community restoration day with Te Kohuroa Rewilding, an initiative focused on engaging people in conservation efforts in Te Kohuroa Matheson Bay. I met the founder, Frances Dickinson, and discussed the importance of community buy-in for long-term restoration success. The restoration day was a partnership with a local freediving club and had community members join for a morning of culling kina. The pilot program for community action and restoration began in late 2024. It was exciting to be a part of this event and see people really engaging with active conservation work. It was also a great opportunity to use the freediving training I did a few months prior! Te Kohuroa Rewilding is the first community group to be given a special permit to remove kina for restoration purposes, and I am looking forward to following its progress.

During my time with the Shears Lab, I had discussions with Dr. Nick Shears about scaling up restoration efforts. Integrating scientific research, policy advocacy, and community engagement (like Te Kohuroa Rewilding) is key to creating sustainable solutions. There is a growing movement to protect these vital ecosystems, but it must be balanced with commercial fishing pressures and increasing public engagement. While the lab makes great efforts to include social, cultural, and economic factors (part of the reason I was so drawn to this project), I really gained insights on how challenging it is to do this kind of well-rounded work and how important outside partnerships are to make change.

Beyond the restoration work, this trip was filled with unforgettable wildlife encounters. During field days, we spotted Bryde’s whales feeding, common and bottlenose dolphins, and a mola mola.

One night, I had the chance to go kiwi-spotting, an experience that my younger self would have never believed. One of my favorite books as a child was about how the kiwi lost its wings, so seeing these birds up close was so exciting for me!

Other highlights of this trip were trying kina (which I really enjoyed–it has such a unique flavor), exploring around Goat Island, and going sailing for the first time!

Seeing the tangible impact of kina removals and learning more about Aotearoa New Zealand’s kelp forests was truly inspiring. A huge thank you to Dr. Kelsey Miller, Dr. Nick Shears, and the entire lab for welcoming me into their work and teaching me so much about kelp restoration. This experience deepened my understanding of marine conservation and left me hopeful that, with continued effort, we can restore balance to these critical ecosystems.

Thank you to the Our World-Underwater Scholarship Society and our sponsor Rolex for making this scholarship experience possible. I would also like to thank Reef Photo and Video, Nauticam and Light and Motion for my underwater camera setup as well as Aqualung, Fourth Element, Suunto, Halcyon, and DUI for my diving equipment.