Despite all the prestige, travel and opportunity that comes along with my role as the 2021 North American Rolex Scholar, it has its fair share of challenges as well. Coordinating which opportunities are available, doing reports, budgets, logs, countless emails, all while still keeping your focus on the main tasks at hand is pretty much a full-time job and can be tricky to maintain. I still struggle with it now, but even though it can be a lot, it’s doable and overall what the scholarship requires. However, when you throw a global pandemic into the mix, things can really get sticky quickly.

After having a wonderful time on Catalina Island, I returned to the mainland in LA feeling inspired and ready to jump from one island to the next. Thanks to one of my contacts through the Scholarship, I learned of a month-long opportunity to do some coral research on an island just south of Tahiti known as Moorea. The project, led by Dr. Nyssa Silbiger of Cal. State Northridge, was going to be looking at how marine coral metabolism is affected by the discharge of fresh groundwater. With most of my own background being grounded in freshwater invertebrates, I felt like this was a great project to get involved in, as it bridged my previous freshwater work with my desire to branch out into more marine-related subjects. In terms of my scholarship goal to get more marine-related research under my belt, it was a perfect fit. Of course, it also helped to know that the research site was renowned as one of the most lush and beautiful places in the world. Regardless of the project’s location though, I was pumped and eager to go on my next adventure.

Originally, we had planned for me to meet up with Nyssa’s grad student, Jamie, at the airport and for the two of us to fly out to the French Polynesian island together a few days after my arrival in LA. Sounds simple, right? Well…since it was an international flight, there was a bit of red tape regarding getting a QR code at least six days before the flight out. Other than that, though, the only other real logistical issue was making sure we had a negative PCR Covid test result. Since I was fully vaccinated, it should be an easy enough threshold to cross … or so I thought.

With my flight leaving late Sunday evening, I did as recommended and found a free PCR COVID test near where I was staying and got tested three days prior to my flight. Typically, after getting a COVID test, results become available fairly quickly depending on where you get your test done. For the place I went to, they claimed to give results within a 24-hour timeframe after getting tested so I wasn’t worried. I explored around LA, met up with some friends and did some sightseeing. I saw the art museum and the tar pits. I visited the downtown library and biked around.

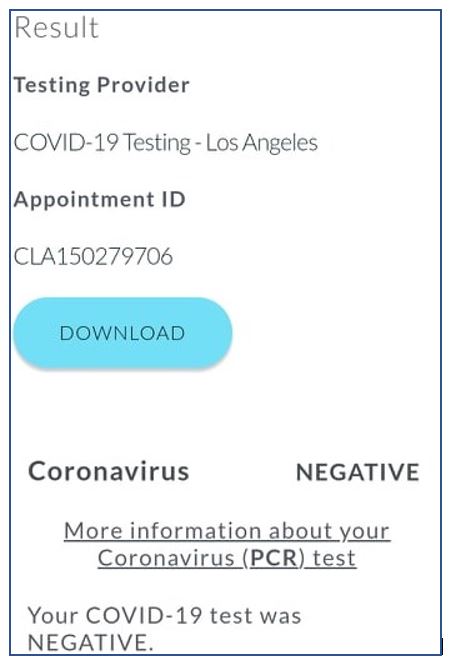

Yet, as the weekend slowly ticked on by, I still had not received my results. I wondered what was taking so long and why I hadn’t gotten any results yet. Trusting in the system, I waited patiently, looking at my phone every few moments with the hope that my results would suddenly appear in my email, but to no avail. Before I knew it, the day of my flight had rolled around, and still, I had no test results. Even so, I made my way to the airport, met up with Jamie for a moment to let her know what was going on, and waited behind the checkpoint, holding out hope until I could wait no more. Worried, I called the clinic to investigate, only to learn that there had apparently been a backlog and that they weren’t sure when my results would come in. In my frustration, the only suggestion they could give was to let the airline check-in staff know what had happened and that I was vaccinated. I did not think this stunt would work but I tried anyway. Of course, it didn’t work; proof of a negative test was required. With my flight only hours away, no idea when my Friday test results would come in, and no way to get a free one that wouldn’t take more than a day, I had one choice left, which was to pay a hefty fee to do a rapid PCR test. I cringed at the financial blow but bit the bullet and paid for the test that would give me results in 45 mins. That would leave me 30 mins to check in to my flight. It would be tight but at least I would still have enough time to make it. Sitting on a bench, my heart fluttered when I finally got an email. I opened the link, logged in, and looked at my result… Positive.

It took me a moment to register but once it sank in, I was devastated. I couldn’t believe it but there it was, staring me in the face. From there it was a cascade of embarrassing and sad phone calls and messages. I had let Jamie, Nyssa, my Scholarship Coordinators, and even the airline folks who I had just tried to convince to let me through, know that I had to cancel and refund my flight because I had contracted COVID. Completely crushed, I dragged myself back to where I had been staying and from there quarantined for two whole weeks. As one might imagine, it was terrible. I developed a fever, got stir crazy cooped up for two weeks, and got an additional slap in the face when my Friday test came back two days after the fact as a negative. Seriously?! Despite all that, after a while, I was able to function again. Once I started feeling better and my quarantine was coming to an end, I took a series of COVID tests until I finally had a negative result. Around the same time, I talked with Nyssa and my coordinators about revisiting my plans to go to Moorea. I knew that even if I wouldn’t be able to stay as long as originally intended, I didn’t want to miss out on such an amazing opportunity. I soon rebooked my flight to Moorea with a new game plan and before I knew it, I was ready to go!

My flight itinerary was simple. I would leave LA with an hour layover in San Francisco before my final flight to Tahiti where I would take a ferry to Moorea with Nyssa and some other researchers who were arriving on the same day. It was a perfect plan and as I brushed my teeth that morning, excited to finally be on my way, a giant filling popped out from the back of my tooth. It seemed that unfortunately, I would still have some trials coming my way. Still, I wasn’t deterred. After resigning up with my new QR code and negative COVID test in hand I made my way to the airport for the second time, and this time I even managed to make it to the actual gate! Finally, it seemed like things were going to work out until I realized that I, as well as the other passengers, had been at our gate for almost an hour longer than we were supposed to. Apparently our initial flight was delayed by an hour and a half. I hoped that when the first plane finally arrived, perhaps they would hold the second plane for us for if we weren’t too late. But the flight arrived almost two hours later, and I knew there was no hope. The plane I was supposed to take to Tahiti was gone and the next available flight would not be until three days later, which just so happened to be the perfect amount of time for me to need yet another COVID test. I was absolutely floored at how my luck could be so bad.

Once again, I had to tell Nyssa and everyone else that I wasn’t going to make it and replan my whole trip. I remembered feeling angry and defeated, but thankfully there was a silver lining here. San Francisco happened to be the home city of my scholarship coordinator Alison LaBonte and her partner (and coordinator by association) Bob Day. Despite everything that was going on, I was happy to finally meet them face to face. Sadly, that wouldn’t last too long though, as their plans the following morning would take them out of town for the rest of that week. Nevertheless, to my thanks, they let me stay at their beautiful place and offered up their bike for me to use. Now I would have to face the challenge of not only finding another free Covid testing center that wasn’t booked and could give quick results, but I also needed to find a dentist that could replace my tooth filling before I left, especially if I planned to dive or snorkel in Moorea. Not only that but I would have to figure out how to get to the dentist’s office on a bike. After dozens of phone calls, I somehow managed to find the necessary places and rode the bike out to each, getting my tooth filling fixed and a free rapid PCR test in one day. After reregistering to get the proper QR code for the third time in a month now, the last piece of the puzzle was once again my test result. Would it come in in time? Well, it did. The only problem was that this time when I opened the results in the Uber on the way to the airport, it showed a big, fat INCONCLUSIVE.

I have no idea how my head didn’t just completely explode from atop my shoulders but somehow it was still there. Of course, this meant that I had to once again pay to get a rapid PCR test that would have results within 45 minutes. At this point, I was ready to fight whatever otherworldly entity or gods that were having a laugh at my expense, but I was thankful that after 30 minutes my super pricey test came back negative. After almost three weeks I finally had everything I needed, and with that, I wasted no time getting on the plane that would, at last, take me to Moorea.

In order to get to Moorea, it’s easiest and cheaper to fly into Tahiti and then take the ferry to the smaller southern facing island. Thus, when I first arrived, I landed late at night in Tahiti and stayed overnight. At the crack of dawn the next morning, I met up with one of Nyssa’s team’s lead technicians and student, Danielle, at the docks in order to catch the ferry to Moorea. Once we landed and got off the boat, Nyssa soon came to pick us up and took us to the UC Berkeley GUMP research station. The station was situated right on the water in the midpoint of the middle inlet of three inlets which together made the island look like a slightly misshapen dinosaur footprint straight out of Jurassic Park or (if you want to be real nerdy like me) like the Phoenix Force symbol from X-Men.

A google image of what the island looks like

The site was gorgeous as everywhere you looked only immaculate mountains, lush rainforest, or calm crystal blue waters could look back at you. It was truly breathtaking. Everything there looked like it belonged in an office calendar or a screen saver. I was absolutely floored by how stunningly beautiful it was.

Call National Geographic

Once we got out of the car, Nyssa gave me a quick tour of the station and showed me where the labs, dorms, dive lockers and water/ sample tables all were. It was nice to finally meet and talk to her in person after all the email communication we had had in the past few weeks. After showing me around and suggesting a place to get some groceries, Nyssa offered me the chance to rest up or, if I wanted, to go to the field site which was where she was headed. Without hesitation, I opted to help. Even though I was tired, in that moment I felt like I had been out of the action for long enough.

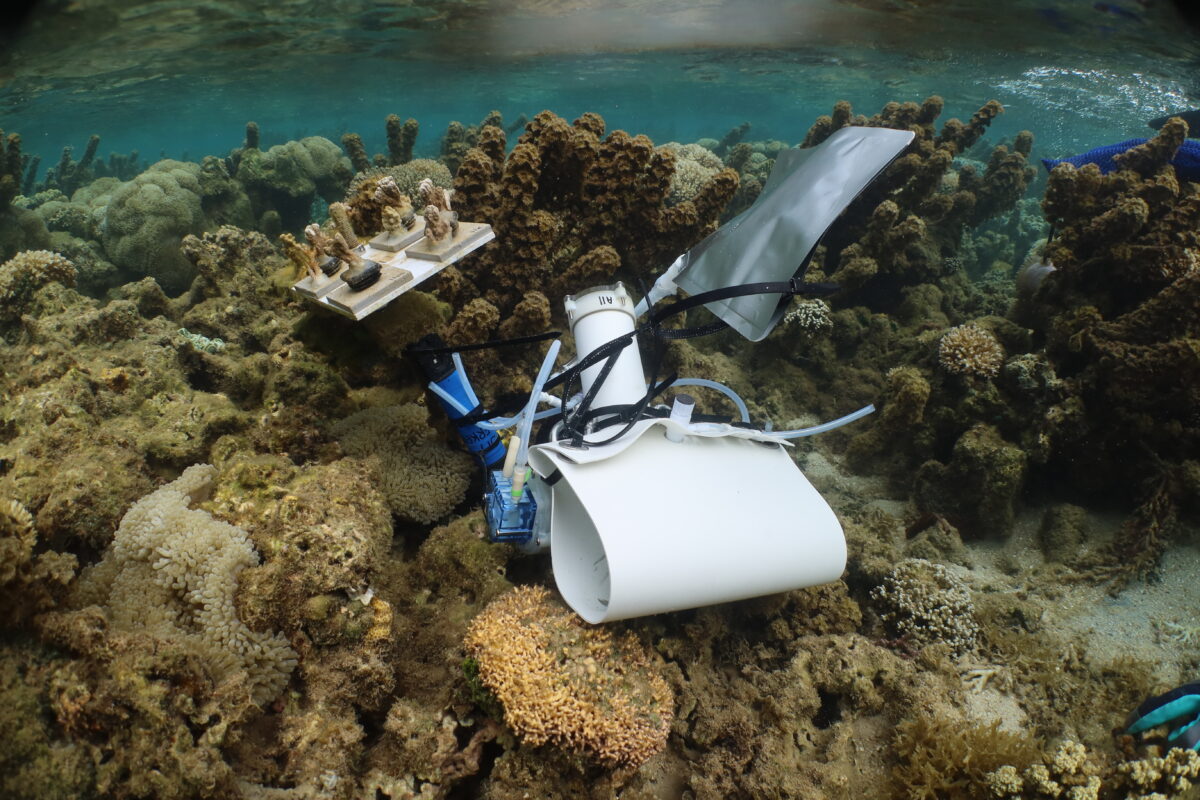

The site was about a thirty-minute drive west from the station and on the way, Nyssa went over some of the details of what the overall project was about. There were various facets of the research, but she talked about how, in general, the team was going to be looking at marine coral metabolism in the presence of fresh groundwater. First, it was important to collect and sample the water that was surrounding the coral. To do this we were going to be setting up several Sub-surface Automated Samplers or SAS’s and dispersing them at previously designated sites on the reef. Originally designed by researchers at NOAA’s Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory (AOML) and the

University of Miami, the T-shaped PVC devices, once calibrated, are able to able to take two water samples as well as record the time, date, and temperature of the samples taken. They were very important parts of our project and once I arrived it would be my task to help put them together.

Once we arrived, I could see that they had set up camp at a small Airbnb facing the ocean and were constructing the SAS’s collection system. My first task was to help with tying and securing the covering that would protect the Tedlar bags that would collect the water samples and attach the zip ties and sandbags that would hold the SAS’s while underwater. It was great to just jump into the project and feel useful. While I was there, I got to meet some of the other researchers that were working on the project and even got to reintroduce myself to Jamie, who I had met briefly at the airport weeks ago. I met up with Maya Greenhill who was a Fulbright scholarship recipient and a ball of light. I also met acclaimed videographer Shireen Rahimi who was there to document the work we were doing. She was kind enough to help me learn a little bit more about my camera, which I attempted again to try out on the reef once I had some downtime. I even got to swim around with some black-tipped sharks and watched the sunset as we worked! Though it was a busy day all around I couldn’t have asked for a better one.

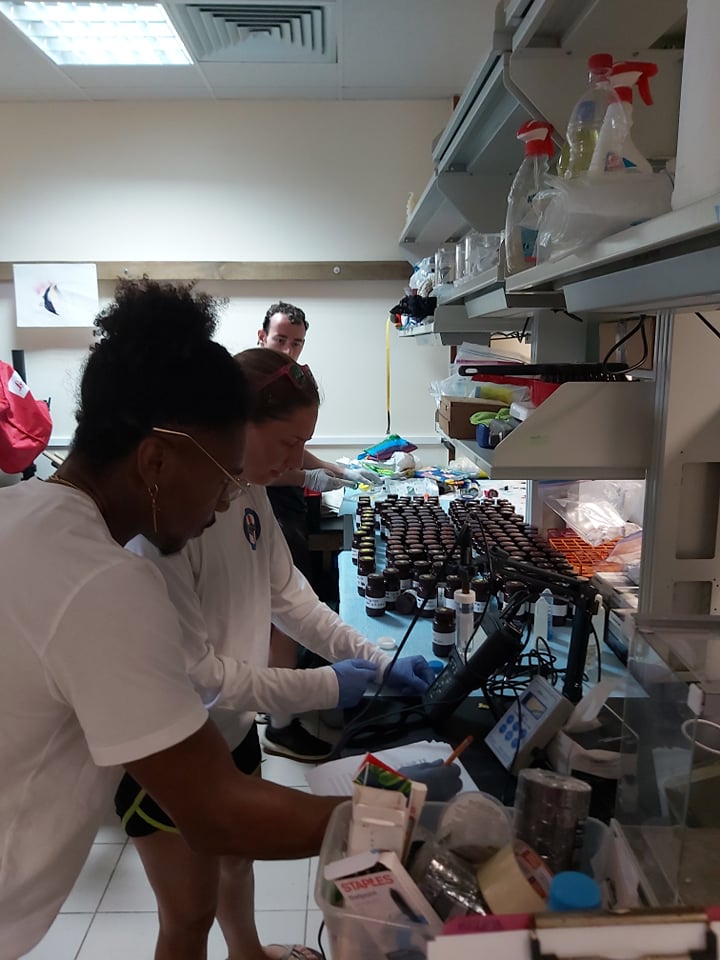

Each day after that was filled to the brim with things to work on and do. I remember that in our email correspondence, Nyssa had mentioned that the workload would be intense, and she certainly wasn’t lying. We started the majority of our days around 6 to 8 in the morning and worked until the sun went down at around 6 or 7pm; some days we even worked many hours past that. Often our time was spent going out to the field to collect coral samples or SAS devices or in the lab, recording what was collected and conducting experiments. In the lab it was great to learn more about how to collect and record the data. Nyssa showed me how to take measurements of the salinity, temperature, and pH of the water around the corals. However, I mostly worked with Jamie and helped her with her side project looking at coral respirometry. In the mornings, Jamie and I would go out to one of the two research sites and use the GPS to find and collect small coral fragments from a reef that had been tagged by Jamie earlier. When we returned to the field station, we would label and measure the fragments. Afterward, we attached the coral fragments to small black screw-like devices and deposited the collected samples into a water table to be used later in our respirometry experiment.

Despite all the jaw-dropping beauty that was surrounding me every morning, it was my time in the lab working on setting up the respirometry experiment that became one of the most memorable, taxing, and fulfilling parts of my time in Moorea. The goal of the experiment was to detect and observe the rate of metabolism or in the case of corals, photosynthesis with varying degrees of light. To start though, Danielle first had to show Jamie and me what to do. In order to set up the experiment, we started with a large styrofoam cooler filled with filtered seawater and added a water pump as well as a heater to set the water at 27.3 degrees Celsius. We then utilized a respirometry stand. The stand by itself looked like a little table with circular wells in it. Each well would connect to a cylindrical plastic chamber that was designed to hold and isolate the coral fragment. Within the well and underneath each plastic chamber was a motor that used a magnet to churn the enclosed water in each cylinder. Over the top of the cooler, we erected a rectangular light that could be fine-tuned in order for us to control the intensity and brightness. Then draped over the lights we also set up a pair of probes for each of the chambers to not only distribute oxygen but to digitally translate and quantify the rate of photosynthesis once the corals were placed inside.

For this blog, I’ve greatly simplified the process but in general, merely setting up the experiment took about 5 hours (and that doesn’t even include running the experiment). Not to mention the first time we tried to set up the experiment there were several malfunctions. It was a long and arduous process just getting all the parts together. However, once we finished we finally ran the experiment and placed the corals in the chambers. Of course, that was a time-consuming endeavor in itself as we had to troubleshoot anything that was going amiss. For instance, it was important that we make sure there were no bubbles in the chambers so that we could take accurate volume measurements afterward. Once everything was properly running, we did several trials testing corals with different light intensities. Each of these trials (I think there were 7) took about 20 min. It was definitely an all-day event. There was one day that Jamie and I had been working so long and late into the night that the bright lights from the project almost made the view from outside the lab look like there was a cool party going on. Despite all the challenges, though, I really enjoyed working in the lab and helping with Jamie’s project.

Besides, even with all the work I still managed to get some fun activities in as well. I went hiking in the lush wilderness, kayaking at the crack of dawn and to several small soirees with some of the other groups there! It was nice to get to meet everyone and just be in such a beautiful place. I even had a dance party

with Maya and Danielle in the dark when our car broke down one night after being out in the field.

The Coral Crew

Overall, I had many great and amazing experiences and small but impactful moments of fun. With

everything that had happened beforehand with COVID and setbacks, I felt like I had worked so hard to

get there and it was totally worth it. I couldn’t thank Nyssa and her students more.