May has been an absolutely incredible month! It kicked off with a few final exams, one of which earned me my Wilderness First Responder certification – hopefully I won’t be using my new skills this year. I regret to inform you that I had to drop college level Yoga due to poor attendance, which I blame on my scholarship-related activities. On May 8th I graduated as Indiana University’s first marine biology major, and the president of the university even mentioned it during our commencement with a graduating class of about six thousand! We had a fantastic commencement speech delivered by the legendary Quincy Jones who had more than a few words of wisdom, and then just two days later I was on my way to the balmy Dominican Republic.

I’ve been working in the Dominican Republic with IU’s Office of Underwater science for four years, working on my personal research and helping out with the various research projects and marine park development activities that the Office conducts. This year I went back to help out with diving safety and oversee the marine biology students attending our field school. Not only did we get back to essentially every marine protected area that we’ve been working in, but we literally created a new marine park! The model that my professor, mentor, and (former) boss, Charlie Beeker, has been creating is dubbed ‘Living Museums in the Sea.’ The Dominican Republic has an incredible wealth of submerged cultural history all around the island, ranging from prehistoric sites, to 16th century shipwrecks, to slave-carrying ships and the only known pirate wreck in the Caribbean, just to name a few! Rather than excavating these cultural resources and permanently removing them from the sea, Charlie appreciates the value they hold in situ. As historically significant sites, the shipwrecks help afford protection to the entire ecosystem that they are now a part of. While protecting marine habitats in developing countries can be difficult, protecting cultural resources is comparatively easy, affording protection to adjacent reefs that would otherwise be left unprotected and unmanaged. In addition, these wrecks are tourist hot spots, bringing in economic benefits to the local communities. By leaving the wrecks where they sank, or in some cases replacing salvaged artifacts into the ocean, and creating marine protected areas around them, Charlie is essentially creating museum exhibits in the sea that benefit the local environment and economy, and help both locals and tourists understand and appreciate the significant submerged cultural heritage of the country.

The site we were focusing our efforts on for this field school was first established in 2004. The Office dropped four cannons that had been salvaged by treasure hunters back into a reef environment off the Southern coast of the Dominican Republic. In 2009 they went back to relocate the cannons closer to the reef, hoping to encourage coral recruitment on the artificial substrates (which you might remember was the focus of my degree research on a nearby site). This summer we brought two more cannons to the site, along with an assortment of related artifacts including cannon balls, galley bricks and broken ceramics.

During the excavation of the Captain Kidd 1699 wreck I was lucky enough to ‘ride’ a 300-year-old cannon back to shore as it was towed slowly behind our boat. This year I got to add two more cannons to the tally. The cannons were waiting in shallow water where Charlie had dropped them a week earlier. We strapped a 4,000lb lift bag to them, one at a time, and dragged them out to deeper water before starting the tedious 1-knot trip to the site. Driving any faster would drag the lift bag underwater, causing it to compress and lose its lift capacity, allowing the cannon to sink almost immediately and, in a worst-case scenario, bring the boat down with it! Charlie and I tagged along on the back of the cannon for a bit, making sure the rigging was secure and the lift bag wasn’t leaking, before floating back to the second boat and heading to the site ahead of time. Dropping cannons is definitely less-than-elegant. Step one: position over a sandy area. Step two: deflate the lift-bag slowly. Step three: stand back and watch the cannon sink at about 30 ft/sec! Once it’s on the bottom, moving it to the desired location is more of an art. Getting the cannon neutrally buoyant and horizontal can definitely be tricky, and as soon as an overeager diver pulls the cannon up a foot or two – enough for the lift bag to inflate just a bit – it’s on its way to the surface! The result is a constant filling and venting of the lift bag, and sometimes a tedious twenty minutes of dropping the cannon to the sand when it becomes too buoyant and slowly filling the lift bag to get it back to neutral buoyancy, ‘walking’ it toward its destination the whole time! Ultimately we positioned our two brand new (very old) cannons on the site and our biology and archaeology students went to work getting baseline documentation of the artificial substrate, cementing artifacts to bare patches of reef to create permanent habitat for reef critters, and determining and documenting biological monitoring stations around the site to monitor the reef’s overall health in the future.

One glaring problem throughout the whole trip was the presence of lionfish. Lionfish were released into the Atlantic in Florida several years ago, presumably during a hurricane. Since then they’ve spread rampantly throughout the Caribbean & Atlantic – as far south as Bonaire and as far north as North Carolina. The lionfish are a huge problem: they reach sexual maturity after a month, have no natural predators in the Caribbean, and are capable of devastating juvenile fish populations and growing as much as 2 cm per day! Their only potential predators would be large groupers, which are entirely overfished in the region, and their prey have no idea how to avoid the lionfish as they’re not used to their presence. In short, they’re an environmental disaster that has the potential to wipe out reef fish communities within a few years. Their proliferation over the past couple of years has been entirely unprecedented. The St. George, a trans-Atlantic freighter sunk as an artificial reef, is a popular recreational dive adjacent to one of our research sites. Last year the local divemasters told us that there were two lionfish on the wreck. We encouraged them to get rid of them, but unfortunately when we returned this year there were a reported thirty lionfish on the site. In the Guadalupe preserve, where I conducted my research, we spotted six more lionfish. And we even found one huge adult on the new Living Museum site we had been working on this year. In countries like the US, Cayman Islands, and Bahamas, there is infrastructure in place at the governmental level to control invasive lionfish. In the Dominican Republic, however, no such thing exists. After the local dive shops and hotel owners talked to us about solving this invasive problem, we decided to take action immediately. We crafted a couple of nets from drywall liner, steel wire, wire screen, and PVC pipe and got to work. In the countries I mentioned, trained professionals typically do the collecting. In the Caymans, local dive shops are now assisting after their staff is given proper instruction. In all of these cases, the lionfish are delivered to some sort of governmental environmental office where they are dissected so that scientists can determine what makes up the majority of their diet, how much they are eating, etc. The lionfish are typically brought to the surface live, euthanized, and sent off to the managing body. The St. George rests in 135 feet of water, with its deck sitting at around 100 feet. Consequently, as Chief Lionfish Control Officer (CLCO), and even with a bit of tricky net-work I was only able to snag two big lionfish and bring them to the surface on our first dive, leaving 28 behind! We were going to make one more dive on the St. George, so obviously this method wasn’t going to cut it. We enlisted John, the owner of Scuba Fun, the dive shop we work with while we’re in the country, to join us for a lesson in lionfish control via the direct percussion method. Now before you start judging our methods I owe you some rationale. First, in a country where no infrastructure for studying the captured lionfish exists, there is no real point to bringing the fish to the surface. Second, while the direct percussion method may sound inhumane at first glance, bringing a fish to the surface from 100 feet results in the rapid inflation of its gas bladder and a slow, upside-down asphyxiation in a hot bucket at the surface. If you want to argue that this is a more humane method, I’m all ears! With a lionfish population exceeding 30 individuals in a 200m2 area, capturing them one or two at a time was not really a viable control strategy. Our final rationale for in situ extermination was that we were returning the biomass to the local environment. Within about 30 seconds, small reef fish were feeding on the lionfish carcasses. Hopefully some of the juvenile grouper we spotted will grow up with a taste for lionfish! We left our homemade nets with John and signed him on as temporary CLCO.

After an extraordinarily productive week with our largest field school ever (17 students) we said goodbye to our budding underwater scientists and said hello to National Geographic Television. One of the ongoing projects of the Office of Underwater Science has been the excavation of Christopher Columbus’ fleet of ships lost in a hurricane in the early 1500s. Due to the remote nature of La Isabela on the north coast, the difficulty of excavating in the Jell-O-like substrate and the prohibitive time requirement (not to mention the plethora of other fantastic projects that have sprung up around the country) the Isabela project has been on hold for several years. This year, however, we’re getting right back into it and bringing Nat Geo along to make a TV documentary.

The first European settlement in the Americas was at La Isabela, on the north coast of the Dominican Republic. When Columbus arrived in the country, he discovered an indigenous population called the Taino. The resulting colonization of the country proved brutal and essentially ended in the extermination of the Taino, an advanced, sea-faring population whose culture still pervades today’s world (barbeques, hammocks – both invented by the Taino).

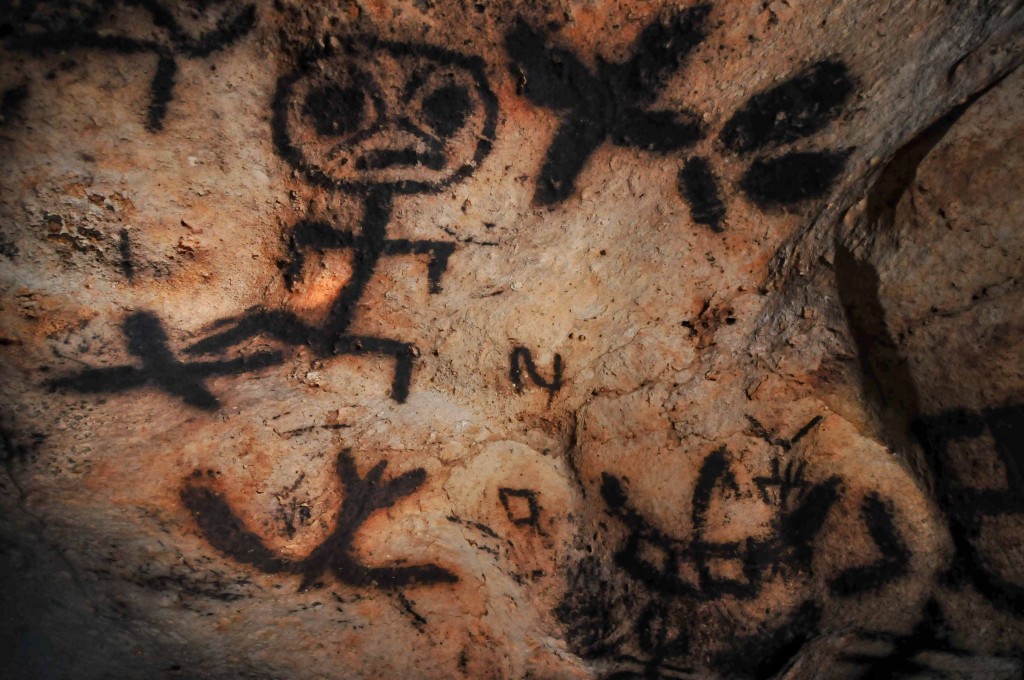

Our first stop with Nat Geo was the Jose Maria cave in Parque Nacional del Este. A two-hour, hot, humid, mosquito-infested hike was a small price to pay for the absolutely astounding payoff. As with many other cultures, caves held a strong cultural significance for the Taino. In many caves and caverns throughout the country one can find Taino petroglyphs and pictographs, but none could possibly compare to the artwork seen in Jose Maria. John Foster, the former State Archaeologist of California, and Juan Rodriguez, former director of the Museum of Dominican Man, two experts on Taino culture and long-time friends and colleagues of Charlie, joined us in the cave. The three interpret the paintings not only as artwork, but also as a story told by the Taino to preserve their legacy. The first thing we saw as we wiggled through the narrow entrance to the cave was a petroglyph known as The Guardian, which is found in all of the caves used by the Taino. The Guardian protects the entrance of the cave, and is struck by the last rays of the setting sun, indicating that if a Taino was to venture any further into the cave, a torch was needed.

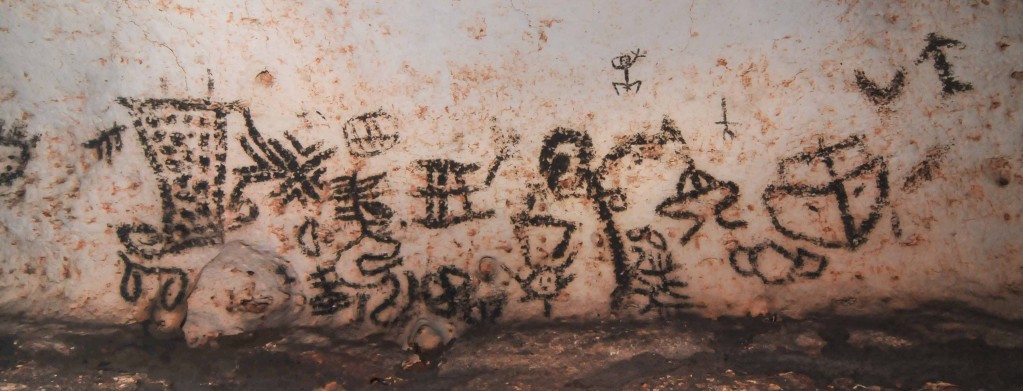

The first room was extraordinary in itself. Massive columns that would have taken hundreds of thousands of years to form towered above us, and stalactites and stalagmites covered the floor and ceiling like giant teeth threatening any who dared enter this sacred Taino site. As we made our way further back into the cave, more and more cave paintings appeared on the walls and in hard-to-reach places that a Taino scribe would no doubt have had to drastically contort his body to reach. Eerie faces stared back at us wherever we shined our lights, and as we turned a corner the cave opened up high to the right, revealing an extraordinary painting of a frigate bird in the upper reaches of the cave. Climbing up to investigate proved incredibly easy, and I could envision the Taino artists stepping in the obvious footholds I was using, five hundred years earlier, their path illuminated by torch light instead of high-powered LED head lamps. The summit revealed a small room absolutely covered in paintings, from figures and faces to frigate birds and what appeared to be crosses. I reluctantly made my way back down and walked further back into the cave, which opened up into a cavernous, cathedral-sized chamber. The paintings in this room were strikingly different. Previously in the cave, the paintings appeared to stand alone – to be perhaps more of artistic or religious significance. These scenes, however were obviously drawn in sequence: there was no doubt that the Taino were telling us a story.

With the coming of the Spanish to the New World, an era of oppression previously unknown to the indigenous peoples all throughout South and Central America began. Truly brutal and horrendous acts were committed, and the Taino were ruthlessly murdered for their religious beliefs. Unlike the Spanish, the Taino had lived on the island for centuries and knew its secrets intimately. They fled from the Spanish into the thick tropical forests, but when this no longer offered sufficient protection, they were forced to take refuge in the caves that they considered sacred.

John, Charlie and Juan have interpreted one particular scene as the Taino’s documentation of the Spanish arrival; the story of the end of their world. The scene depicts the Taino treaty with the Spanish in which the Taino agreed to provide food to the starving colonists in return for peace. Next is an image of the comparatively merciful hanging of a female Cacique, or Taino chief. The twelve male Caciques of the island were locked in a hut and burned to death after being invited by the Spanish for peace talks. The most striking pictograph, however, was without question the image of a Spanish caravel sailing directly toward the viewer. An image which, to the Taino, must have signified the beginning of the end of the world as they knew it. It felt eerie walking through the cavernous room, imagining frightened Taino men, women and children living in hiding and in absolute darkness a hundred feet below the surface. Their stories painted on the wall were no doubt a last effort to preserve their culture into the future. And there we were, a very privileged few, reading the last testament of a people who were literally exterminated by European colonization and intolerance. We spent the two-hour hike out absorbing the significance of what we had just experienced.

The next day we had barely recovered from the grueling hike, but we took off bright and early to go diving. While the Columbus shipwrecks rest on the north side of the island, there is a unique site on the southern coast near our annual field research sites. Cannons were the weapons of mass destruction of the day. When Columbus sailed to the Americas, he was outfitted with some of the first cannons, called bombards. Only five sites in the world were discovered with bombards on them. Three of these sites were salvaged by treasure hunters, and one was excavated by archaeologists, leaving only one example in the entire world of Columbus-era bombards that are still in the ocean where they were dropped 500 years ago. This site, on Caballo Blanco reef, is extraordinarily rough. Charlie believes that a ship ran aground on the reef and dropped the two bombards and two anchors over the side in order to lighten the load and float safely to the other side – no evidence of an actual shipwreck has ever been found on or near the site. Following through with the luckiest-guy-in-the-world trend, I got to film all of the underwater footage at the site for the National Geographic Special! And when it couldn’t possibly get any better, they invited me back down in July to finish the underwater filming at La Isabela during the excavations! This being the industry I’m interested in starting a career in, I can’t tell you how privileged I felt to be filming for National Geographic.

Leaving the Dominican Republic was easy, knowing I’d be coming back just a couple of months later. I arrived back in NYC on a Friday afternoon, and Saturday morning I took off for Dutch Springs with my new DUI drysuit to check out the DUI Demo Day event. Faith and Dave of DUI helped me get my new suit sorted out, trimmed the seals so that they were a perfect fit, and threw me in the water only to come out… dry. Sunday I took off for D.C. to attend the Smithsonian symposium on scuba and scientific diving. There were lots of familiar faces, including Ingrid who flew all the way over from Norway! But even better, there were a ton of new, interesting people to meet and some incredible presentations on research all around the world that has been facilitated through the use of scuba. I hopped a train back to NYC on Tuesday night, concluding a fantastically, absurdly, ridiculously busy two weeks. I’ve had about a week in NYC to unpack, get some final things sorted out and get all of my cold-water gear together before heading off to South Africa for the World Cup! Err, I mean the Sardine Run!