Coral reefs have got to be the number one reason the majority of humans decide to start diving. Destinations that can offer visits to these spectacular structures generate a revenue that boosts a considerable amount of economic productivity. But few are those that know much about their reefs and act to protect them in such a rapid-growing and changing planet.

In Puerto Morelos, there is a marine lab branching from the National Autonomous University of Mexico, or UNAM, that studies the local reefs and is working hard to preserve them. One particular species of coral, Acropora palmata, the elk-horn coral, is of great concern to the region as the populations are plummeting and up to only recently has there really been an effort to understand why and prevent further decline.

Acropora palmata reproduces sexually once a year, following the cue of the full moon and the temperature of the ocean. In this spectacle, the corals release an egg-sperm bundle that dominates the water column, in the hopes of successful fertilization to produce a new polyp – the individual coral unit – that will get planted far away to start a new colony. The lab in Puerto Morelos works in collaboration with SECORE to collect these bundles to culture millions of larvae in conditions that are controlled for better spawning. I was received by Dr. Anastazia Banaszak, who runs the coral reproduction project and C O R A L I U M, who gave me a tour of the facilities and explained to me a little about what her students are doing.

Most of their work revolves around managing successful in vitro fertilizations and providing suitable structures for the polyps to cling to so that they can begin colonizing. They have been experimenting with several shapes and have to monitor the polyps closely as they are in a significantly fragile state. With these efforts we hope that the small coral colonies can be reintroduced into the ocean and continue growing in their original habitat.

After my visit, I took the ferry to Cozumel island, one of the major tourist destinations in Mexico. Here I met German Mendez, a marine biologist that overlooks Cozumel Coral Reef Restoration Program. German talked to me a little more about coral biology and their importance in the ecosystem. We went over some brief planting and brushing techniques and plunged straight into the water to look for the coral structures that he has been maintaining over the past couple of years.

German’s work focuses on restoring and saving the few remaining reef structures in the port of Cozumel and adjacent beaches, which have been all but wiped out by in and outgoing cruise ships, urban development and unknowing and careless divers. We swam to the some of the recovery sites and did basic maintenance. We brushed the corals carefully, got rid of the excess weeds and algae covering them and placed them bundled together to support coral formation.

In addition to this, German taught me how to prepare the epoxy used to place coral fragments back into a reef structure to keep them put. In the last 8 years German’s efforts have greatly increased the number of coral structures alive and have taught a greater number of tourists and volunteers how to protect the reef. I was able to appreciate the distinct line between the reef adjacent to the cruise ships and the one that was only a couple of meters away. The more healthy reef has an interesting presence of urchins which help munch away the excess algae, and has more diversity of corals. German’s job is clearly more demanding on the cruise ship reef, but nonetheless has managed to keep the few remaining colonies alive.

Following my visit to Cozumel, I hopped on a plane and flew to Huatulco, a small town in the state of Oaxaca, which served as my hub for the next two weeks. Every day I took a van that dropped me on the side of the road an hour-and-a-half later near the fishing port Puerto Angel, where the the Universidad del Mar is located. The state of Oaxaca placed this university here as part of their strategy for bringing higher education to more rural areas, as opposed to having all education opportunities concentrated in major cities.

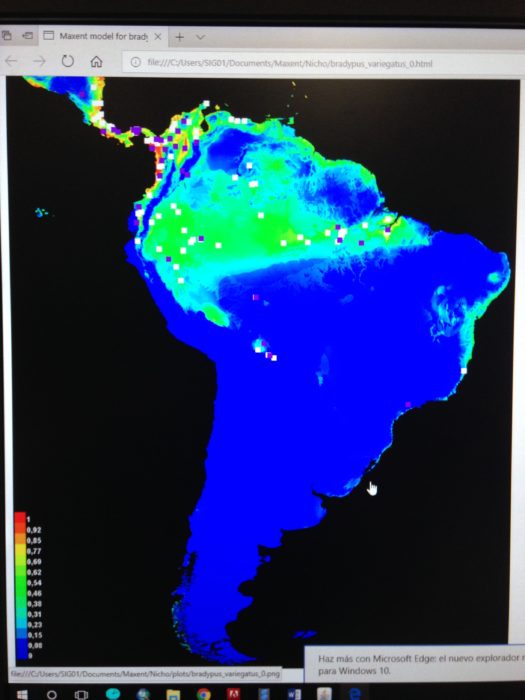

Here I volunteered at SIGALT, the geographical information systems (GIS) and remote sensing lab. At SIGALT I took a basic crash course on GIS and remote sensing, with a focus on marine case studies. I was able to see how the lab utilized spatial technology to map and model interesting topics, such as that of ecological niches.

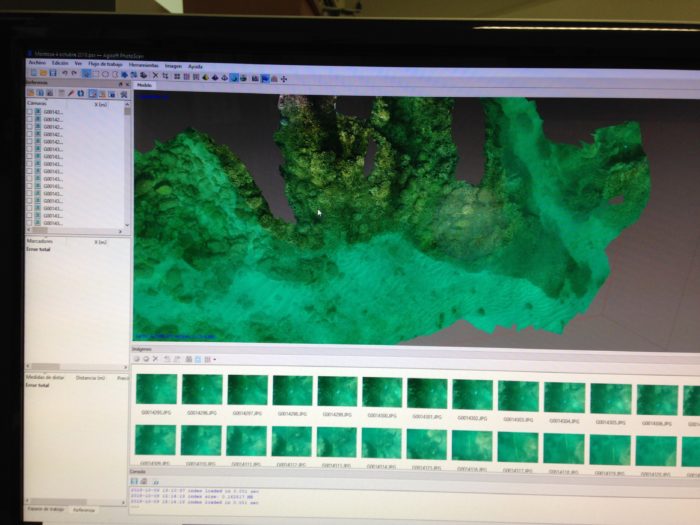

I also helped conduct fieldwork and process data, where we deployed data loggers to record temperature and light information and performed photogrammetry techniques to model the local reefs. This was one of the most exciting activities as I was able to use the data to help build some of the models that the students will use for their theses. Despite the ongoing storms that provoked persistent power-outages at the computer lab, we managed to build some of the best models that the team had done to date. It was really surprising to witness the results we were getting considering the limited resources available to the students, compared to other projects that I have helped out with that benefited from top-end technology.

I am excited to continue this collaboration with SIGALT in the future because it opened up a new field of study for me that has so much potential to be explored. We may even be able to present our results at the national coral reef conference next April. But meanwhile, check out some of the models we made!

It goes without saying that a university lab dedicated to the study of spatial analysis would of course possess a drone. Well with SIGALT I had the opportunity to document an event that occurs every year in Mexico, which I myself had never seen before. Gulf turtles arrive by the dozen to the soft and cozy beaches of Oaxaca to lay their eggs. The scene is so massive that it can be quite gruesome, as it calls for a feast to many. The presence of the turtles attracts thousands of birds, crabs, dogs and humans. But nonetheless the amount of turtles that reach the shores far outnumbers that of their predators.

For the arrival to be considered an official landing there must be at least 1,000 individuals on the beach, where it is not uncommon for the beaches to endure the arrival of 30,000 turtles in an afternoon. With the help of SIGALT and their drone, we were able to document the arrival and help count the number of individuals. This way scientists can cover a larger area and make more accurate estimates of the number of turtles arriving each year.

Thank you to the generous hosts and sponsors!

Our World-Underwater Scholarship Society